Special Report:

As America’s pet insurance industry goes mainstream, do companies insure themselves or you?

May 19, 2021

Pet insurance in America is going mainstream. The question is now more a matter of how. Earlier this month, pet insurance companies reported a 27.5% increase in total premium volume in the United States in 2020 over 2019, a growth rate that rivals any industry, including e-commerce.

In April, our report on how a once trusted, legacy pet insurance brand, Petplan, broke the faith of loyal pet parents who signed on during its founding era provided unsettling hints to a question now looming for the pet insurance industry:

Is pet insurance worthy of consumer confidence?

In the same report, we offer hopeful answers, too, by comparing Petplan’s tailspin trajectory to maverick insurance business Trupanion, as well as to just-launched, self-described disrupter Lemonade.

The good news for the pet insurance industry in the U.S. is that it is growing rapidly. The bad news is that more dog (we don’t acknowledge cats) owners spending more money means more attention is now being paid to what consumers of pet insurance are getting for their money. Among those now paying attention are a group of otherwise obscure state insurance regulators, part of a sub-committee called the Pet Insurance Working Group, which is part of the NAIC (National Association of Insurance Commissioners). In other words, the historic growth and activity in the pet insurance world gives the regulators more to do – and puts them under more scrutiny.

We report their deliberations below amid an astonishing new State of the Industry report from NAPHIA, the trade group that represents more than 99% of pet insurance companies.

But, first, a caveat: Daniel Schwarcz, a law professor at the University of Minnesota and one of the country’s leading insurance law and policy experts, has spent much of his career writing about insurance industry practices that deceive consumers. And he doesn’t think the regulators have shown much gumption when it comes to protecting consumers.

This paper, for example, explores homeowners’ insurance. Like pet insurance, policies and plan options are varied and have significant differences even within carriers. Yet, even Schwarcz’s research assistant is unable to obtain a sample policy from the company or find the policy on the company’s website, demonstrating how even educated consumers are prevented from “reading the fine print.”

Our reporting on the same issue and practices at Nationwide last year has gone unanswered. Here is an excerpt from that report addressing Nationwide’s Keep-Away practice:

3/19/2020 “Your dog’s health insurance can be better than yours, if you pick the right insurance” There appears to be a directive in place instructing customer service/insurance agents not to send even sample or boilerplate pet insurance policy language to any individual who is not a policyholder. In other words, prospective customers cannot request sample policies. And it’s not as if the website makes it easy to find a copy of a policy…There was little or no information on the company’s website about obtaining a full-text copy of a policy to read before enrolling. Nationwide senior spokesman Adam Fell and spokeswoman Karen Davis declined detailed requests for comment when asked why policy texts are not provided prior to purchase and about discrepancies between the policies. Davis did point us to a link that, in fact, does provide policy materials, but we could not find the link ourselves from the website’s main page. After several failed attempts to locate the policy materials ourselves, we tried to sign up for a rate quote on the presumption that, perhaps, providing the website with contact information would prompt an email containing policy materials and options, but after we entered information, we were taken to a screen and prompted for credit card information…. This is especially important because Nationwide’s pet insurance plans vary dramatically based on cost. There are endless options as far as type of plan, coverage, tier….

The company has continued to decline requests to comment when asked why call center agents tell prospective customers to complete enrollment in order to obtain policy information. Note to consumers: Many policies can be found here at SERFF.com, the NAIC’s System for Electronic Rates and Forms Filings, but even a knowledgeable consumer is unlikely to know about SERFF.

In a recent interview with Schwarcz, he says the regulators bear more responsibility than even the insurance companies for the situation we highlighted at Nationwide, where call agents told us they are prohibited from distributing sample policies to non-members even though when we identified ourselves as reporters to the communications people, we were immediately provided with policy materials.

“It also, to me, speaks to some of the real problems with the insurance regulators,” Schwarcz said. “They’re responsive to certain types of things. Like they’re responsive to specific consumer complaints. They’re often responsive to federal pressures. But if it’s just a matter of making sure that a market is well-regulated and functioning the way that no one complains about it, they don’t address it. And so, there aren’t a lot of people complaining…it just doesn’t really rise to the level of attention.”

“It’s ridiculous,” he said of Nationwide’s practice. “You’re selling a product. You’re not telling people what the product is,” he said, addressing a common industry excuse for not publishing policy material, which is ‘concern over intellectual property theft.’ “It’s patently ridiculous. And it’s just a super obvious and easy thing for state insurance regulators to try to fix.”

In fairness to Nationwide, we should point out that Petplan does not publish sample policy language anywhere on its website. In fact, Nationwide actually does publish sample policies on its website, though they’re impossibly difficult for a consumer to find.

*UPDATE* Following publication, a reader informed us that, in fact, Petplan is now publishing sample policies here. If Petplan and Nationwide were to add “Sample Policies” — directly linking to the policies — to the main menu tabs…

The Regulators’ Agony

It’s April 29, 3:55 p.m. with five minutes remaining of the virtual meeting of the first Pet Insurance Working Group of state regulators from across the country in more than a month. As of about 90 seconds ago, Matthew Gendron of the Rhode Island Department of Business Regulation has introduced another proposal: “So,” Gendron concludes, “We think that [pet insurance] operates a lot more like health insurance, like consumer health insurance.” Gendron has just proposed, in the last minutes, that the pet insurance industry be reclassified as health insurance and de-classified as property/casualty insurance. The change would have broad, even calamitous, ramifications for the industry. Insuring property is not nearly as fraught with consumer protection issues as insuring health. For example, someone who is wrongly denied health insurance and then gets sick or dies because he or she was unable to get care has a much greater claim for damages than someone who has a property insurance claim.

“I’m talking about waiting periods, we’re talking about preexisting conditions and exclusions, and co-payments, co-insurance, all the things,” Gendron says. “It sounds like health insurance. It’s marketed in a similar way to health insurance. It operates like it…So, for all those reasons, we think it’s worthy of a conversation to change the overall line of business for pet health insurance.”

The working group chairman, Donald Beatty of Virginia, sighs. With three minutes remaining, he launches into an impressively cogent response that effectively but tactfully tables Gendron’s proposal.

The model law, as the regulators’ committee has currently drafted it, is not a magic bullet, but it requires all kinds of disclosures from insurers that address many of the pitfalls we’ve addressed in past reporting and we’ll discuss here in the context of what has been an unprecedented, historic year of growth for American pet insurance as well as expansion.

American pet insurance turns 40

In most wealthy countries today, the concept of paying out of pocket for health care is unusual because most wealthy countries have strong universal health care insurance systems, some government-controlled and all government-mandated for universal coverage. Pet insurance is an easier pill to swallow, more easily absorbed within a culture where health care isn’t something you debate. It’s something you get, like a passport.

On May 4, after almost 40 years of pet insurance in America, the North American Pet Health Insurance Association (NAPHIA) reported that the number of American dogs covered by insurance by the end of 2020 was about 3.1 million, up from 2.52 million in 2019. Even more significant, the market penetration rate for American dogs (that is, the percentage dog owners who bought insurance for dogs in 2020) clocked in at 3.4%, up from 2.8% in 2019, according to NAPHIA, the industry’s trade group.

Pet Insurance in American Historical Context:

“Cowboys don’t ride buses.”

Why pet insurance has taken more time to catch on in the U.S. is a frequently explored topic among pet insurance industry folk. One theory is that VPI (Veterinary Pet Insurance), the country’s first pet insurance product, founded in 1982 and frequently described as a clunky, not-so-friendly-to-consumers product with its benefit schedules and limits, failed to win hearts and minds. Maybe, but Americans feel similarly cynical about non-pet insurance products. So, what’s different about pet insurance? The answer is arguably not much apart from timing; the American identity and historical context add significant challenges to anyone in the business of selling any insurance product to U.S. consumers, full stop.

Born out of revolution, American life continued to be defined by political, social, and economic change well into the twentieth century. Though livestock was essential in everyday American life, America lacked the kind of social and economic underpinnings that existed in pre-industrial Europe. In fact, as the first pet insurance business model was being explored in Sweden in the 1890s, Frederick Jackson Turner was writing his “Frontier Thesis” about Western expansion, which argued that western expansionism and frontier culture were giving rise to a new American identity defined by rugged individualism.

Pre-industrial Europe offered sophisticated agrarian economies out of which a market grew for products that helped people control the cost of health care for livestock; thus, Sweden was a likely birthplace for “pet” insurance. Today, the vast majority of pets in Sweden are insured. In the U.K., pet insurance started in 1952 where, today, about 25% of pet owners there buy insurance. The U.S. pet insurance market penetration rate, when cats factor, remains under three percent.

Vets and insurance companies agree to disagree over key regulatory language

As of the April 29 meeting, it had been more than two months since an embarrassing and contentious February 18 Working Group meeting. At that session, the insurance companies’ opposition to a more narrow definition of “pre-existing condition” that was more favorable for consumers forced insurer Trupanion to break publicly with NAPHIA, the insurance trade association, in support of the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). The insurance trade group’s positions on pre-existing condition language would have been uniquely troubling for Trupanion, which thrives on its relationship with the veterinary community.

In substance, that debate about how to define “pre-existing condition” never amounted to much more than public declarations of values – different values, that is.

The AVMA seemingly made consumer protection a top priority. But the insurers’ trade group, NAPHIA, had contended that without the freedom to be “flexible” with its use of pre-existing condition language, the industry’s bottom line would suffer. The AVMA’s leaders, including Janet Donlin, General Counsel Isham R. Jones, and Chief Medical Officer Gail Golab have declined repeated requests to discuss the “compromise” the two parties reached.

That “compromise” was presented at a virtual meeting on March 4. In essence, that “compromise” was agreed-upon language for the “pre-existing condition” definition. The problem, however, is that the new language accomplished nothing of substance that we can identify because the new language hinges on how “verifiable sources” is defined, with verifiable sources referring to the sources from whom an insurer might derive evidence of a pre-existing condition.

Here is the definition as of today:

“Preexisting condition” means any condition for which any of the following are true prior to the effective date of a pet insurance policy or during any waiting period:

i. A veterinarian provided medical advice;

ii. The pet received previous treatment; or

iii. Based on information from verifiable sources, the pet had signs or symptoms directly related to the condition for which a claim is being made”

Importantly, thus far, neither the regulators, the veterinarians, nor the insurance companies have insisted on defining “verifiable sources,” which is what the definition arguably hinges on.

Brandon Bridgeland, an attorney in Boston with the non-profit Center for Insurance Research, is one of two NAIC-appointed consumer liaisons to the Pet Insurance Working Group and almost immediately raised concern about the absence of a definition for “verifiable sources.” More recently, Bridgeland submitted a suggested drafting note to attach to the “pre-existing condition” language that was intended to narrow “verifiable sources.” However, Kate Jensen, representing the insurance companies (NAPHIA) argued that a drafting note was not necessary: “We’re not sure that there needs to be a drafting note because the word ‘verifiable’ means ‘able to be checked for accuracy. It has its own guard rails around it,” she offered. No individual from the AVMA spoke either for or against the drafting note.

As Wagmo omits 10k limit and Petplan tailspins, regulators push forward

This past February, Working Group Chairman Donald Beatty told TCR he was confident that his panel could complete the model law draft by the time the regulators gathered for their national meetings. Those meetings have come and gone–they were in April. He may still be able to finish before the official end of spring, but it’s getting terribly close.

The model legislation, even if agreed on, will hardly solve any single problem in the industry unilaterally and likely will not solve most of the problems. But, if enacted across the states, it would provide consumers, finally, with roadmaps and most important, disclosure—the kind of disclosure that addresses what’s now occurring at NYC-based pet insurance startup Wagmo.

Wagmo sold its first pet insurance policy in the United States in 2020. Co-founded by Christie Horvath and Alison Foxworth, the VC-backed pet insurer is one of few in the market whose only business is pets (as opposed to larger insurance firms that do not deal exclusively with pet owners). Wagmo is also part of the growing group of newcomers – pet insurance startups – in the space. It’s one of nearly a dozen companies to enter the market within the past five years.

Wagmo may not yet offer customers live 24/7 phone support like Trupanion, but co-founder and CEO Christie Horvath personally returns customer email on occasion, which earned the company +2 paws on TCR’s rating scale. Horvath’s enthusiasm for her product was obvious when we spoke in late 2020, and again in May 2021.

But whatever Wagmo’s co-founders’ talents and good intentions, all of their insurance policies currently have $10,000 per incident limits. Worse, TCR was surprised to discover and confirm that the 10k limit was not mentioned, not even referenced, in the Sample Policy published on the company’s website. This is a vivid example of how the new pet insurance model legislation could have a direct impact by adding more disclosure and protections for consumers, thereby facilitating more informed comparison shopping, and raising consumer confidence in the still relatively new industry.

Per Working Group consumer advocate Brendan Bridgeland, here’s exactly where the model law addresses Wagmo’s omission:

Section 4 Disclosures (A) An insurer transacting pet insurance shall disclose all of the following to consumers: (3) Any policy provision that limits coverage through a waiting or affiliation period, a deductible, coinsurance, or an annual or lifetime policy limit…

Redefining Insurance

Trupanion recently announced two lower-tiered insurance products that will compete with other cheaper pet insurance products with one major difference: However inexpensive the pricing structures might be, Trupanion CEO Darryl Rawlings has committed that the lower-tiered products will have the same standards of disclosure under which the core Trupanion product operates.

“In short, we know that some consumers may enroll in brands other than Trupanion, which is OK if they are informed and understand the difference in coverage. If that occurs, we want them to make an educated decision and enroll with a brand that we own that provides high value and is not misleading,” he wrote last month.

What’s the issue with a $10,000 per incident limit?

To be clear, the issues our reporting raised pertain to transparency , not likeability. if such limits on insurance coverage are prominently disclosed and explained to the consumer, nothing is inherently evil. We also want to underscore that Wagmo is one of several examples of insurers that downplays or omits entirely a critical policy limitation. Moreover, Wagmo’s leaders admirably engaged on tough questions about their policy language, which is more than we can say for most pet insurance companies.

To demonstrate how potentially disastrous it is that a consumer might unknowingly sign up for insurance that limits incidents to $10,000, we asked Trupanion for some examples of recent claims that were notably high. They pointed out that not only were all of these claims paid but importantly, they were “paid directly to the veterinary hospitals through Trupanion’s software – eliminating the reimbursement model and the need for the member to put the large dollar amount on their credit card,” Trupanion spokesman Michael Nank said in an email. And large dollar amounts, they were.

The following claims were all paid to Trupanion members within the past 12-18 months:

German Shepard treated for bloat: $16,800

Mixed Breed treated after ingesting foreign body: $11,600

Lab Retriever – bilateral hip dysplasia: $11,700

Mixed Breed treated for Pancreatitis: $12,000

“There are other incidents,” Nank added, “where treatment for certain conditions (cancer, aspiration pneumonia, etc.) are even higher – such as the Mixed Breed that was treated for Sepsis: $40k.”

Importantly, Horvath, Wagmo’s CEO, says that no member to her knowledge has met or exceeded the $10,000 limit in an example like one of the above and we have not found any formal consumer complaints for social media commentary to suggest otherwise. However, Horvath has also declined to provide us with any enrollment data.

With so much growth and so many new insurers each year, the disclosure framework of the pet insurance model law, as now drafted, offers the promise of a new normal: a pet insurance market where consumers can feel more confident and secure in their choices, which is good for everyone, including, over the long term, the insurance industry.

The pet insurance industry, through its trade group, NAPHIA, has not always been in harmony with veterinarians. As noted, the disagreement over how to define “pre-existing condition,” for example, remains unresolved. That gap aside, the regulators, consumer advocates, insurance company representatives, and veterinarians have produced together through Beatty’s state regulators’ group, a draft that, as the example of Wagmo shows, does pack real punch. The disclosure requirements, alone, would force multiple pet insurance companies to reassess the sustainability of are a significant improvement, particularly because the information or a link must be on the insurer’s main home page.

As of May 17, 2021, “The Pet Insurance Model Act”:

PET INSURANCE MODEL ACT – DISCUSSION DRAFT for PET INSURANCE (C) WORKING GROUP Revisions made following April 29, 2021 virtual meeting

Section 1 This Act shall be known as the “Pet Insurance Act”Section 2 Scope and Purpose A. The purpose of this Act is to promote public welfare by creating a comprehensive legal framework within which Pet Insurance may be sold in this state. B. The requirements of this Act shall apply to Pet Insurance policies that are issued to any resident of this state, and are sold, solicited, negotiated, or offered in this state, and policies or certificates that are delivered or issued for delivery in this state. C. All other applicable provisions of this state’s insurance laws shall continue to apply to Pet Insurance except that the specific provisions of this Act shall supersede any general provisions of law that would otherwise be applicable to Pet Insurance.

Much is still under discussion. Regulators are eager to impose time limits, for example, on what’s known as waiting periods, time frames during which the pet owner is expected to pay premiums while the insurance policy completes its “waiting” time, not fully eligible for coverage or in some cases, not eligible at all. Nationwide, for example, has a notoriously long waiting period for orthopedic injuries: six months. Indeed, a sign or symptom arising during the “waiting period” time frame is also considered “pre-existing.”

NAPHIA offered strong opposition to any time limit on waiting periods and to any language that would limit the use of waiting periods. Per the Meeting Minutes: “Ms. Jensen said the length of waiting period varies by policy and carrier, and it also affects the premium price point. She said waiting periods are typically structured for different conditions based on how long those conditions would take to develop. She said NAPHIA does not have consumer complaint records relating to waiting periods because there is robust disclosure of these waiting periods to the consumers.”

At 3:55 p.m., with five minutes remaining for the state regulators scheduled meeting, task force Chairman Beatty of Virginia introduces the proposal from Gendron’s of Rhode Island to reclassify pet insurance as health insurance. The online public meeting is showing no signs of winding down.

Beatty sighs then says, “While, on an academic basis, I think your conversation has some merit, in the real world, for me to amend the accident and sickness insurance code to cover health insurance would be disastrous.

“I would be showing up at the General Assembly,” he continued, “telling them, ‘Well, you know what? …[The pet insurance companies] ‘really don’t want to have to cover autism.’” Beatty talks faster as he runs Gendron’s proposal into the ground, albeit politely as he continues to offer reasons why not:

“This prior approval rate, we don’t want; that will apply to this policy and district guaranteed; no pre-existing conditions. And they really don’t want to have to cover autism. I’m going to open up a whole plethora of issues, many of which have been worked out over two decades between the industry and the legislators and advocacy groups. Everybody’s going to –I’m going to get SHOT when I explain that.”

Needless to say, the proposal to move pet insurance from the Property/Casualty category, where it is inexplicably classified as “inland marine” insurance, to health insurance did not make much headway on April 29.

More to Come

Today, the Pet Insurance Working Group is set to meet again. It’s a packed agenda:

Discuss Unresolved Issues in Sections 3 [Definitions], 4 [Disclosures], and 7 [Pre-existing Conditions] of the Draft Model

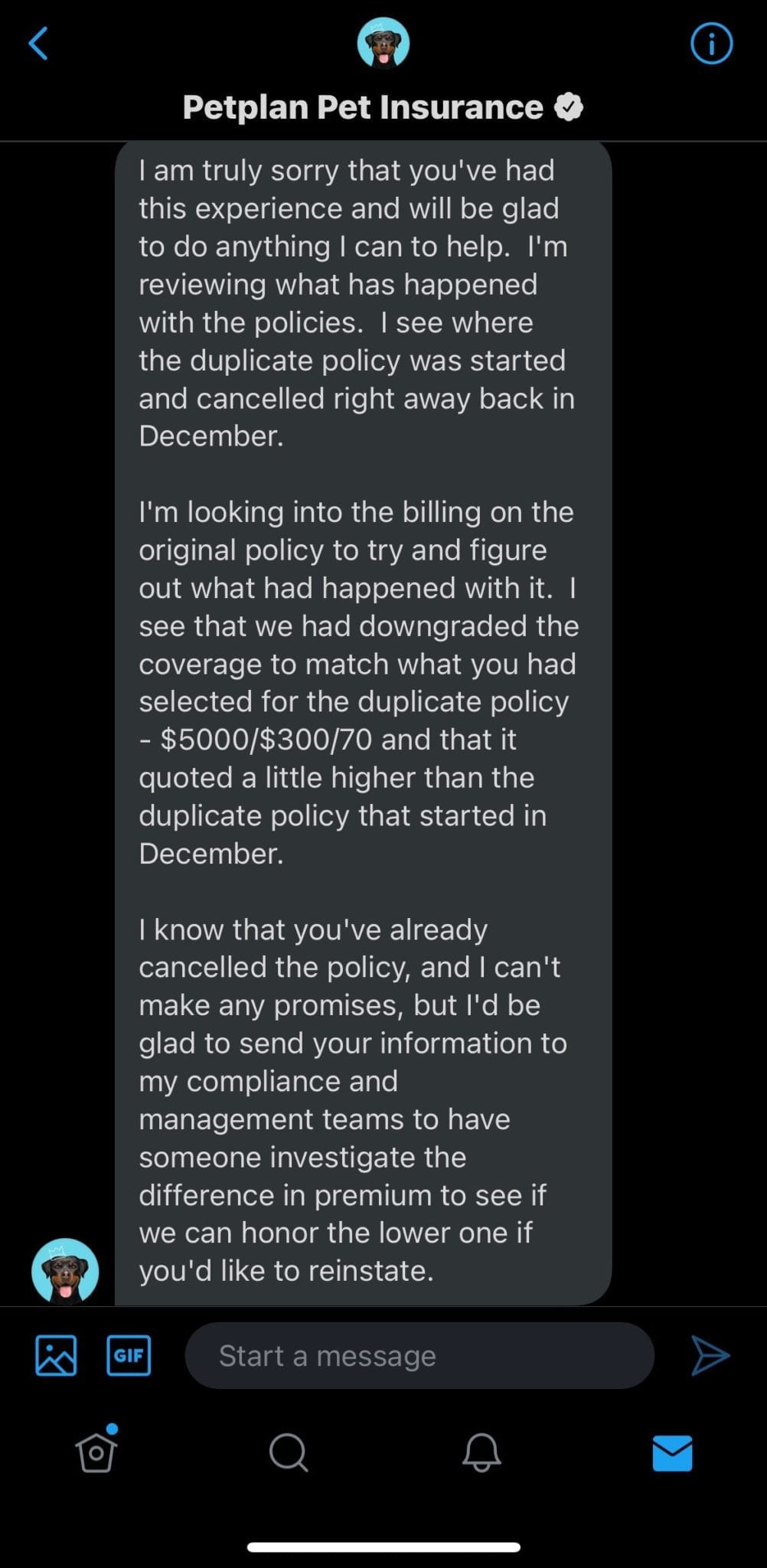

Consumers struggle to understand and navigate health care for their dogs. It becomes obvious that their work is needed now more than ever. Take, for example, these notes a Petplan member emailed TCR a few days ago, documenting his ordeal over the past year which he has corroborated by sharing with TCR contemporaneous screenshots as well as screenshots of messages exchanged with Petplan’s Twitter handle:

9/15/2020 – Started insurance with monthly payments of $56.91.

12/23/2020 – Used Petplan website to update the policy coverages to reduce the premium to $34.99 per month.

12/23/2020 – Noticed that I now had 2 separate policies

Immediately reached out to Petplan asking them to confirm the policy changes as well as asking them to correct the discrepancies with multiple policies.

1/2/2021 – Ashley from Petplan reached out about policy redacted and asked me to confirm updates to the policy and with a new monthly payment of $42.61.

1/8/2021 – I responded back stating that the website gave me the downgraded coverage for $34.99 and not $42.61.

Received no response from Ashley regarding my inquiry about my own policy.

1/10/2021 – Receive email from Christopher McCann suggesting that my policy has been updated. I responded the same day asking about the policy updates made as I had questions that weren’t addressed.

Today morning I noticed that my credit card was charged 2 times for the policy redacted-01 – $53.01 on 4/28/2021 and then again $34.51 on 5/4/2021.

I called Petplan to ask about this and they pointed out the following:

- When I made updates to the policy on 12/23, while the website suggested that I was updating my existing policy, apparently, I was getting a quote for a new dog and that it was my mistake.

- When I was reached out on 1/2/2021, they asked me to confirm the updates to my policy which I didn’t. They went ahead and downgraded my coverage while keeping the monthly payment at $56.91. In their system, I now have lower coverage while paying the same premium.

- The communication from Christopher McCann on 1/10 was about this change that was made to my policy without my consent and without providing any information about the changes made.

That agenda that Beatty and the other regulators — along with representatives from the insurance industry, veterinarians, et al.–may seem dry, and they will continue to work in relative obscurity. But the distraught emails from disaffected consumers like the notes shown above should motivate them – and make all of us want to pay attention.

*UPDATE* Following publication, a reader informed us that, in fact, Petplan is now publishing sample policies here. However, nowhere on Petplan’s main page is there clear signage that directs consumers to the sample policies; a consumer would need to click on “terms and conditions” in the page footer. If Petplan and Nationwide were to add “Sample Policies” — directly linking to the policies — to the main menu tabs, this would meet the standard.