Millions of Dogs May Be Accumulating Toxic Levels of Copper From Commercial Foods

Renowned veterinary liver specialist Dr. Sharon A. Center has published three new studies in JAVMA she says make a compelling case for regulatory action.

A leading veterinary liver specialist at Cornell is warning that at least 12 million dogs across the United States, age 9 or older, may be at risk for serious liver injury; specifically, a condition called copper-associated hepatopathy or “CuAH.” These dogs may be silently accumulating dangerous levels of copper from their food — and, she says, new peer reviewed data offers a compelling case for regulatory action.

Dr. Sharon A. Center, BS, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM), an emeritus professor of internal medicine at Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine, has published three new peer-reviewed studies in JAVMA (Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association) which she says show widespread risk of copper-associated hepatopathy in dogs fed commercial diets.

In interviews with TCR, her first since publishing the new research, Dr. Center spoke at length about the significance of the new data, offering greater insight into each study and its implications. Dr. Center also provided a statement to TCR earlier this week responding to regulators at HHS on behalf of FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine.

INDUSTRY, REGULATORS PUSH BACK

As in the past, regulators and industry are pushing back on Dr. Center’s findings.

The Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Veterinary Medicine declined to comment directly on Dr. Center’s studies. In a general statement, Andrew Nixon, a senior spokesman for the Department of Health and Human Services, said the agency oversees animal food safety through ingredient approvals, inspections and compliance programs, while placing responsibility for safe products “ultimately” on manufacturers. He wrote:

FDA monitors the safety of all types of animal food for all types of animals by reviewing pre-market animal food ingredient submissions, including approving safe food additives for animal food use, evaluating generally recognized as safe (GRAS) notices. FDA uses a comprehensive inspectional and risk-based compliance program to oversee animal foods in the US market. Although FDA is the federal agency responsible for regulating the manufacturing, distribution, and use of animal food products, the ultimate responsibility for producing safe and effective animal food products lies with the manufacturers and distributors of the products.

Dana Brooks, who is the outgoing president of the Pet Food Institute (PFI), the industry’s main trade association, was asked about Dr. Center’s new studies and whether the group would revisit its 2024 position statement, which said there was “insufficient research to establish” a maximum copper limit. In a statement provided last year to TCR, a PFI spokeswoman said the organization did not believe there was a definitive link between copper levels in pet food and copper-associated hepatopathy, emphasizing that copper is an essential nutrient for dogs.

TRADE GROUP CHIEF: “We take [these studies] seriously.”

UPDATE: Following publication of this story, Ms. Brooks provided the following statement:

PFI is aware of these recent studies and is carefully reviewing them. They represent ongoing scientific research that PFI and U.S. pet food makers are continuously monitoring to best support the health and safety of dogs and cats. We take this seriously.

SENIOR VETERINARIAN AT NYC’S ANIMAL MEDICAL CENTER DINGS HHS/FDA COPPER RESPONSE

Dr. Ann Hohenhaus, a senior veterinarian who is double board-certified in internal medicine and oncology; and the director of Pet Health Information at the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center (AMC) in New York City characterized Mr. Nixon’s comments as “conflicting” in a statement provided to TCR:

Mr. Nixon’s comments are conflicting.

In one sentence, he says the FDA is responsible for pet food safety and later says the pet food manufacturer/distributor is responsible. When I look at the FDA’s mission https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/what-we-do#mission I would argue ultimately food safety is the FDA’s mission and they are responsible. Based on their stated mission and the strength of Dr. Center’s publications, the FDA should meet their mission by acting to ensure the safety of dog food.

Dr. Center, for her part, called the FDA’s and Mr. Nixon’s response “unsettling” because, she told TCR, “AAFCO’s standards are wrong.”

Responding to Mr. Nixon, Dr. Center said in an email:

The response from HHS representing the Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM)-branch of the FDA is unsettling.

The recommended allowance for copper in dog foods was determined by a National Research Council expert committee advising pet food standards with the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) monitoring compliance. It does not rest with the pet food manufacturer. Stating that a diet is compliant with AAFCO recommendations is an employed marketing strategy. Presently, copper content in dog foods is shrouded in secrecy by many pet food manufacturers / companies that have relegated copper as a proprietary ingredient—which is preposterous. They cite that their formulations meet AAFCO standards. So, if AAFCO standards are erroneous- what, then ? Our research shows that AAFCO/FDA standards allow hazardous copper intake by dogs. One study also demonstrates safe copper provision in pet foods relegated by AAFCO/FDA as “prescription only” based on copper content below their allowable range.

“What else do we need to clarify to initiate regulatory action?”

SILENT KILLER

Copper accumulation in a dog’s liver is difficult and expensive to diagnose. A definitive diagnosis requires a liver biopsy, which, in addition to being an invasive procedure, can cost more than $10,000 in cities like New York. “Because of expense and procedural risks, many affected dogs likely remain undiagnosed,” Dr. Center told TCR.

Dogs, like humans, can accumulate toxic levels of copper in the liver—but they can remain asymptomatic throughout their entire lifespan.

This aspect of the disease is widely misunderstood, even among veterinarians. Copper accumulation can remain silent for years, Dr. Center said, but may become dangerous if a dog experiences illness, injury or another stressor, similar to humans with Wilson’s Disease (a genetic disorder causing severe and lethal liver copper accumulation unless diagnosed and managed). “Copper augments oxidative injury and circulatory compromise,” she said.

A major indicator of a liver involved injury – though not specific to CuAH – on a routine health check is a persistent and progressive increase in a liver enzyme called ALT, says Dr. Center.

Even veterinarians cannot easily learn about copper levels in most dog foods.

That’s because most pet food labels do not disclose total copper content, and when they do, the information is often cryptic.

The only feasible way a pet owner can avoid a high-copper commercial dog food is to research and identify the small number of non-prescription, copper-restricted diets – such as Voyager, Just Food For Dogs Hepatic Support; Royal Canin’s Labrador Diet – or to use a therapeutic, low-copper prescription food, of which there are only two.

A FAILED PUSH FOR TRANSPARENCY

Dr. Center and her colleagues have been working to address CuAH for decades. In May 2024, an AAFCO sub-committee on Pet Food assembled to address a proposal drafted by Dr. Center and colleagues which would have, at least, initiated some attempt to address problems by allowing pet food manufacturers to label foods as “controlled copper” voluntarily if they limited copper content to lower levels.

According to holistic veterinarian and blogger Dr. Jean Hofve, who says she participated in the committee process, the measures in Dr. Center and colleagues draft proposal were supported by veterinary scientists; however, they were opposed by industry representatives.

Nonetheless, Dr. Center’s recommendations failed.

“The proposal being considered was to allow language on pet food labels for manufacturers who were willing to limit the amount of copper in their foods to the normal minimum, but not in great excess,” Dr. Hofve wrote on her blog.

“Language was proposed for addition to the AAFCO Official Publication for a ‘controlled copper’ claim,” she added. “But the committee meetings were contentious. The scientists in the group (including myself) were in favor of this addition, but the group included individuals representing the interests of the pet food industry, and they were completely against it….The proposed language did win in the working group on a ‘party line vote’ (science vs. profit), but when it got to the full AAFCO committee, the science proponents were rational and reasonable and the industry reps were loud, obnoxious, and not at all hesitant to promote their irrational, exaggerated ‘concerns.’ So naturally the proposal failed.”

In a statement provided to the committee, Dr. Hofve wrote:

“There really is no excuse for the vast overages of copper (and other minerals) in many pet foods. The current minimum copper for growth is 12.4 mg/kg DM, and for adult maintenance 7.3 mg/kg DM. Some foods have tested well over 10 times that level between 2015-2020, according to the Expert Committee report. In one of our meetings, I mentioned that pet foods had routinely test at 300-400% of their minimum requirements. I was challenged on this. But tests of wet and dry dog and cat foods performed by the Kentucky Department of Agriculture in 1994-1995 showed that copper was at 300% or more in well over 40% of dog foods. Note that this was while copper oxide was still in 20use—clearly, ingredients alone were providing sufficient copper in the vast majority of foods. Less than 5% of products failed to meet 100% of the minimum requirement.”

WILL NEW RESEARCH FLIP INDUSTRY’S DEFENSE NARRATIVE?

Now, armed with new research just published in three JAVMA articles last month, Dr. Center is challenging the reasons cited by pet food industry leaders for vetoing the 2023 proposal.

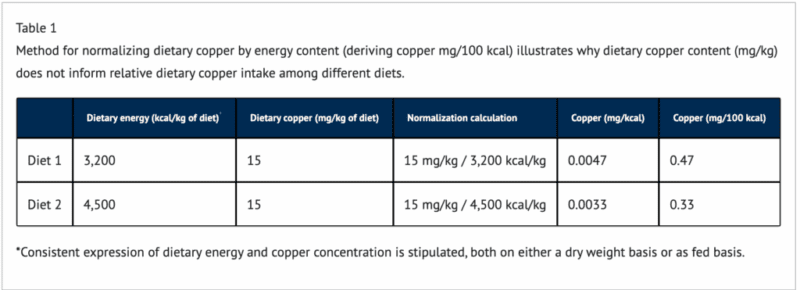

“This issue is further complicated by lack of U.S. labeling requirements disclosing total Cu content in commercial dog foods or treats (foundational nutrient Cu, supplemented premix Cu),” Dr. Center wrote in the discussion section of the study comparing coyotes and domestic dogs. “Even when information regarding dietary Cu is provided, expression on an ‘as fed’ or ‘dry weight basis’ confuses the average consumer. Normalizing Cu content against energy (mg of Cu/100 kcal) as done herein assists product comparisons, as most foods are fed to individualized energy provision. Distressingly, some companies consider Cu content proprietary and will not disclose information, while others seem uninformed.”

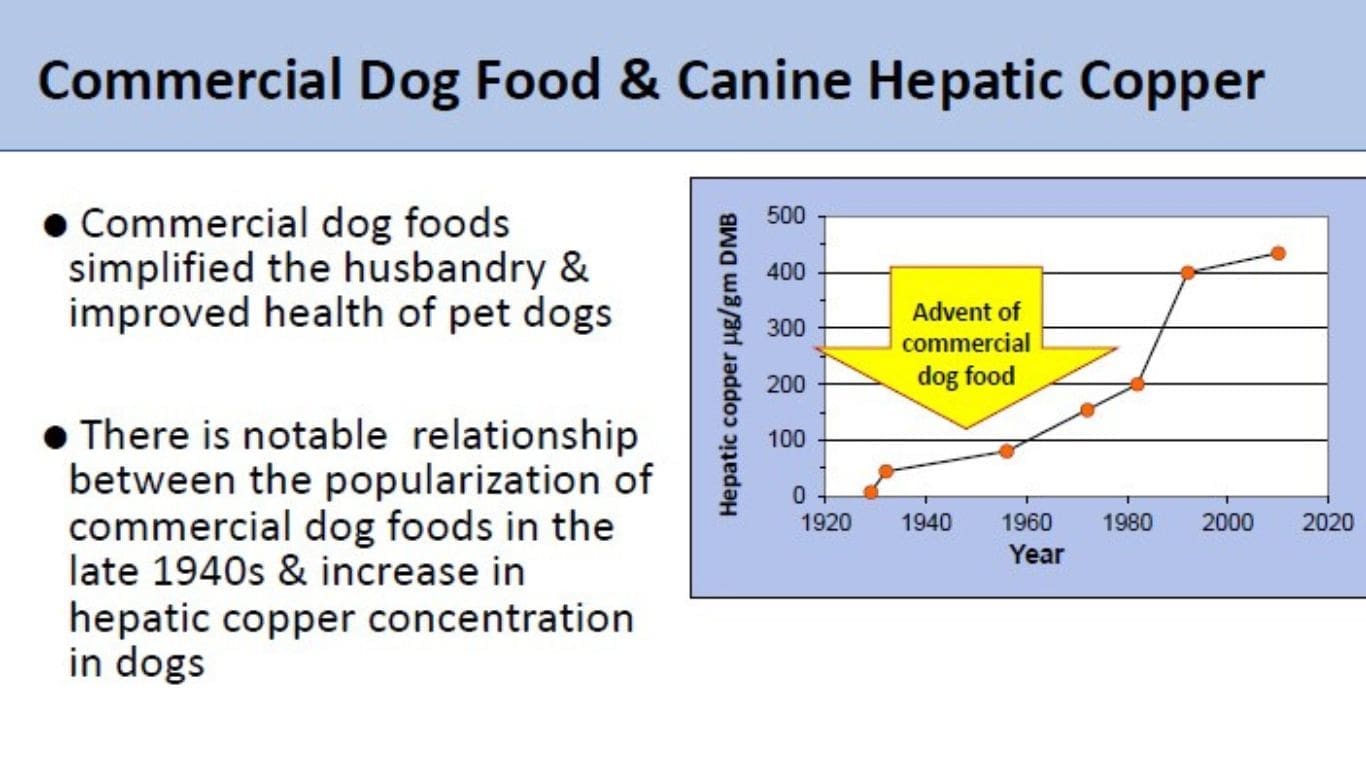

This past June, Dr. Center previewed her new data at an elite annual veterinary conference, the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) Forum in Louisville, Kentucky under the title “Uncovered Truths About Liver Copper Accumulation in Dogs: Additional 2023–24 Studies.”

The three studies, now published in JAVMA – each as “open access” – extend her work, examining liver copper accumulation across typical pet dog populations, comparing liver copper accumulation in dogs to coyotes, and evaluating impact of low-copper diets on lifetime survival and health indicators in dogs.

In the first study, Dr. Center and colleagues analyzed liver samples from 104 senior dogs euthanized for age-related reasons at a major primary-care hospital in Michigan. No dog fed a copper-restricted diet showed dangerous liver copper levels.

38 percent fed commercial diets did.

Liver Copper Accumulation in Dogs fed copper-restricted vs dogs fed copper-replete diets.

- 35 of 91 dogs (38%) fed typical commercial diets had positive rhodanine staining (copper specific stain confirming copper-sequestration within liver cells [hepatocytes]).

- 20 of these dogs (22%) had liver copper concentrations exceeding the upper reference limit of 400 µg Cu/g of dry weight liver (dwl).

- 14 of these dogs (15%) had liver copper concentrations exceeding 600 µg Cu/g dwl, the level at which copper-chelating drugs and lifetime dietary copper restriction are recommended.

- No dog fed a copper-restricted diet had liver copper exceeding 355 µg Cu/g dwl or demonstrated rhodanine positivity. These dogs consumed diets without copper premix additives.

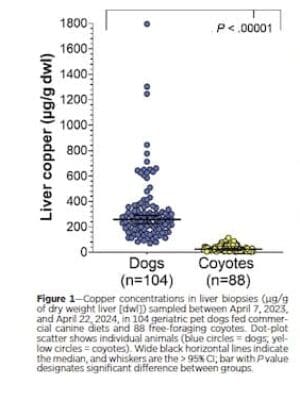

Cataclysmic Control Group: In Second Study, Coyotes Offer Staggering Results

“Significantly higher hepatic copper concentrations in dogs compared to coyotes implicate excessive copper in most commercial dog foods”

- “This study compared liver copper accumulation in 104 pet dogs to 88 free-foraging coyotes using coyotes as a surrogate for a canine species NOT consuming Cu fortified diets. The difference was staggering.”

- Median liver copper concentration in dogs: 248 µg Cu/g dwl significantly exceeded the median liver copper concentration in coyotes: 25 µg Cu/g dwl. No coyote had rhodanine stainable copper vs 34% of dogs studied.

- “Dogs evolved from wolves and can have fertile progeny with several other wolf-like clade species (grey wolf [Arctic wolves, Northern Territory wolves, Serbian wolves, Croatian wolves], European Golden Jackals, and North American coyotes.)” Liver copper concentration in coyotes is identical to other wolf-like clade species except domesticated dogs. Further, liver copper concentration in humans is similar to wolves, golden jackals, and coyotes. “Isn’t it curious,” Dr. Center told TCR, “that other wolf-like clade species and humans have copper concentrations far less than dogs ?–”

- Even dogs on the lowest-copper commercial diets (0.15–0.24 mg/100 kcal) had higher copper accumulation than coyotes.

Study 3: A third study debunks the argument of risk for copper deficiency reasoned by regulatory officials to reject a lower copper minimum allowance, Dr. Center told TCR.

- “There has never been evidence of copper deficiency in pet dogs fed these diets—only assertions from industry influencers,” she wrote.

- “If declining copper content to 0.10-0.12 mg Cu/100 kcal (below FDA/AAFCO regulatory limits) is dangerous, the vulnerable studied population should have shown deficiency symptoms and a negative impact on lifetime survival. The study of more than 200 dogs fed a lifetime copper-restricted diet found no signs of copper deficiency or shortened survival.”

Dr. Center says she hopes the new studies will persuade regulatory officials to revise the lower copper limits; implement a maximum copper limit; and require all pet food manufacturers to provide consumers with a standardized metric — mg Cu /100 kcal — for the copper concentration in all pet food products (See Table 1 Above).

A COPPER MINIMUM, NO MAXIMUM — AND LITTLE DISCLOSURE

For now, despite Dr. Center’s decades of research, the AAFCO copper minimum remains in place. And despite repeated requests by Dr. Center and others, the organization has never set a maximum. Moreover, the industry has pushed back persistently on calls from top veterinarians for greater transparency with respect to pet food labeling requirements in order to help consumers understand the amount of copper in the pet foods they purchase.

The result is a nutritional “Wild West” in which some diets contain five to eight times the copper a dog seemingly needs, says Dr. Center, with no regulatory mechanism to prevent it.