Leading liver vet says there’s too much copper in dog food

Regulators decline to take action as more dogs get sick

The number of dogs now at risk for fatal liver diseases has skyrocketed over the past decade and the culprit is excess levels of copper in commercial dog diets. That’s what the world’s go-to authority on dog liver diseases Dr. Sharon A. Center at Cornell told The Canine Review in a series of interviews between July and September.

There is now a significant amount of peer-reviewed research from Dr. Center and her esteemed colleagues, all of them highly regarded specialists in veterinary medicine, connecting an increase in cases of liver diseases in dogs to excess copper concentrations in commercial dog foods, which causes a condition called Copper Associated Hepatopathy (CAH).

Until recently, diet-related Copper Associated Hepatopathy was a condition vets only worried about in dogs with a genetic predisposition such as Labrador Retrievers and Dobermans.

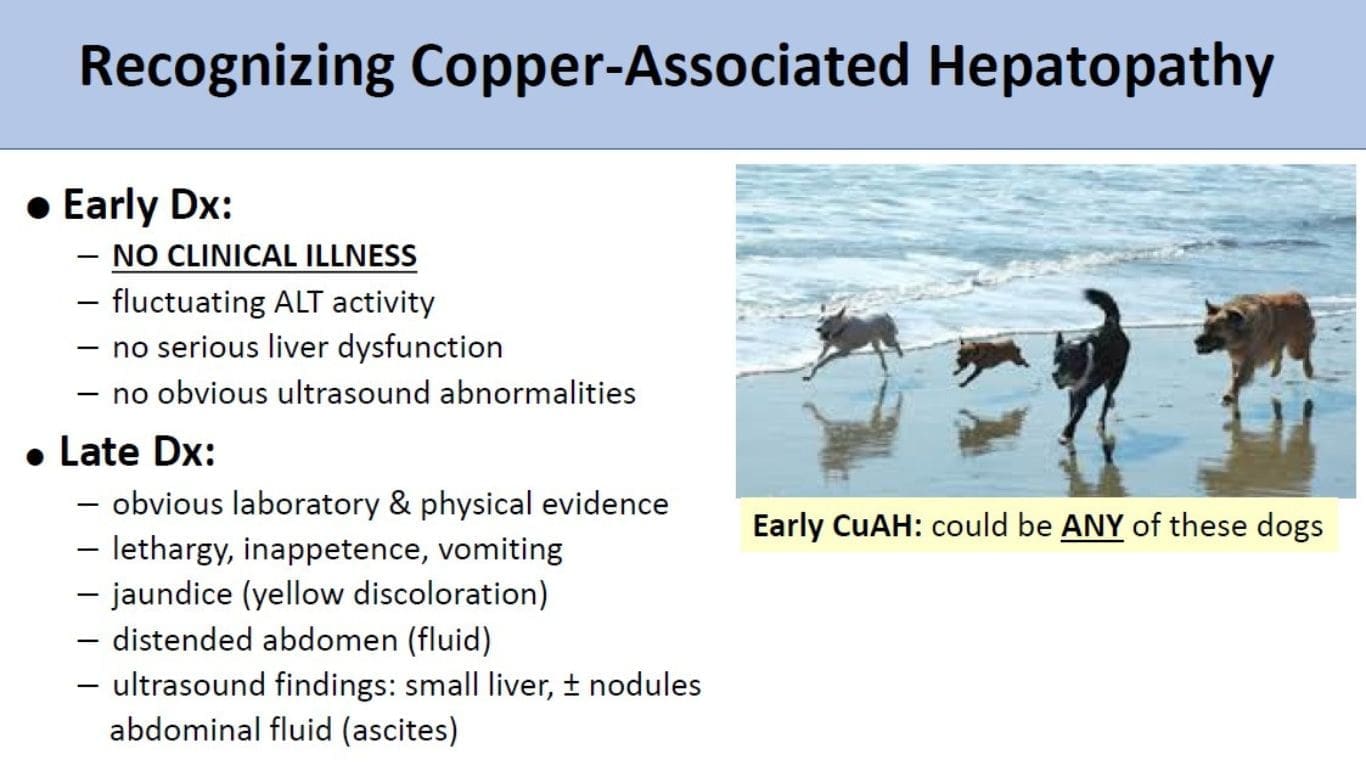

The problem is now so pervasive, any dog is at risk, vets are warning, including dogs with no known predispositions to liver disease.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO), a nonprofit organization responsible for enacting FDA recommendations for labeling and content in pet food, are aware of the increase in diet-related copper illnesses, yet continue to insist that more research and data are needed to change copper content in commercial dog food.

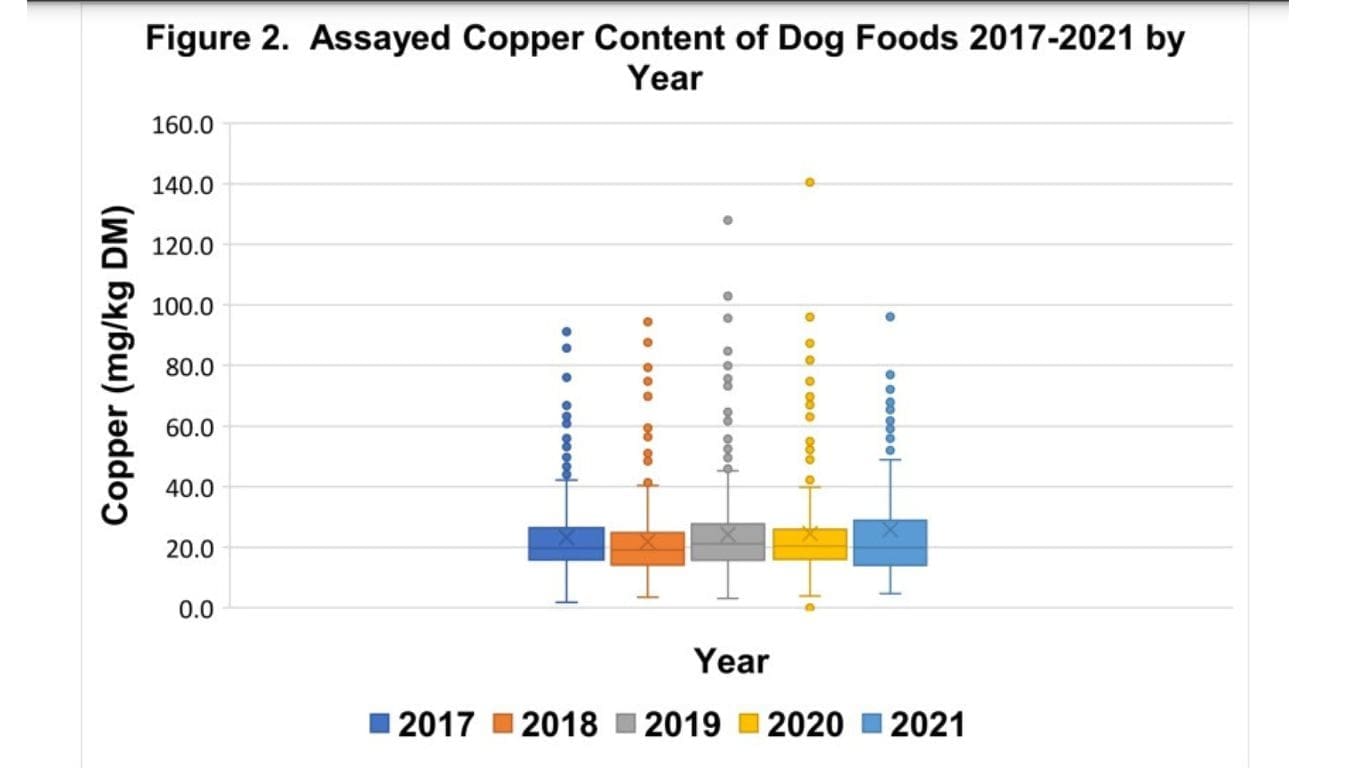

Copper Content of Commercial Dog Foods 2017-2021

-

The data in the chart below represents the copper concentrations in the designated years in commercial pet food brands.

-

The outliers demonstrate values as high as 20 times the level of dietary copper concentrations leading vet specialists say is safe.

-

These data points represent dietary copper concentrations in over-the-counter dog foods likely still available on shelves today.

-

Any dog in the United States eating a commercial diet could be eating the foods represented by the dots. Exactly which diets contain outlying high copper concentrations remain unclear to consumers.

A High Visibility Problem

Copper storage diseases and copper in dog food have retained high visibility in veterinary circles since the February 2021 issue of the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, when Dr. Center and her colleagues published a “Viewpoint” article documenting the connection between increasing amounts of copper in dog food and a rise in cases of canine liver disease:

Over the past 15 to 20 years, we have seen what we believe to be an increased incidence of copper-associated hepatopathy in dogs. The onset of this increase appears to have coincided with a change in the type of copper used in premixes added to commercial dog foods. And, more recently, the increased incidence may have been exacerbated by consumer-driven desire for pet foods formulated with a high content of animal-based ingredients, including certain organ meats, that might introduce additional copper and by trends favoring foods containing vegetables with a high copper content (eg, sweet potatoes). In light of the increased incidence of copper-associated hepatopathy in dogs…we believe that it would be prudent to reexamine dietary copper recommendations for dogs and reconsider current guidelines for copper content in commercial dog foods.”

Less than a year later, in January 2022, Dr. Center declared copper-associated liver disease a danger to all dogs—no longer only for certain breeds with genetic predispositions to copper storage diseases such as Dalmatians, Dobermans, and Labradors.

Today, there is no regulatory framework in the United States that imposes or even encourages a maximum level of copper in dog food.

In 2015, a minimum amount, 7.3 mg Cu/kg DM (dry matter) was established by AAFCO and the FDA to ensure dogs consumed copper, an essential mineral for all mammals. However, for most vets concerned with high copper content in food, including Dr. Center, there is a consensus that a minimum is “Looney Tunes,” as one expert phrased it to TCR, and, rather, it is a maximum that is desperately needed.

A 2021 presentation to FDA Public Listening Session on Pet Food Oversight

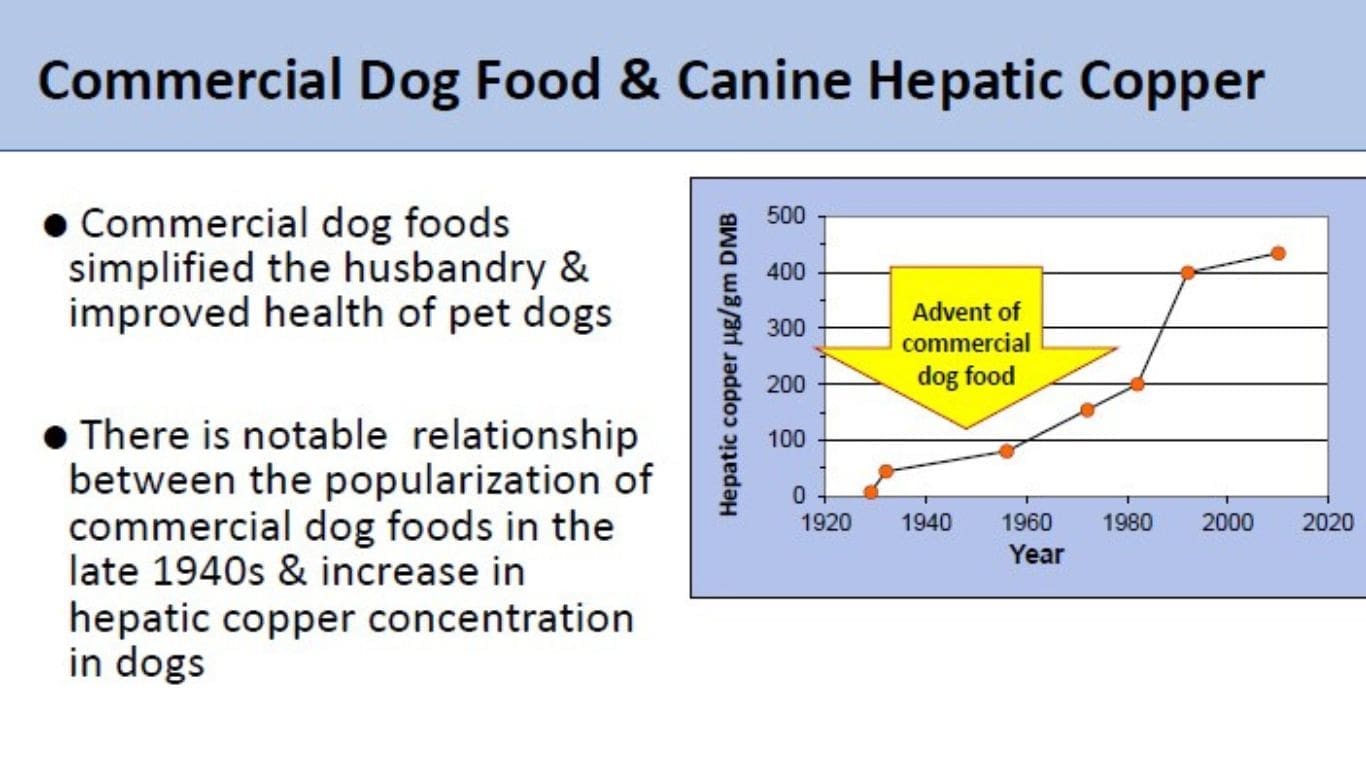

- Copper Hepatopathy Working Group • SA Center, DVM, DACVIM (Cornell University) et al. Copper Hepatopathy Working Group • SA Center, DVM, DACVIM (Cornell University) et al. Chart shows directly proportional relationship between the increase in commercial dog food brands starting in the 1940s and Canine Hepatic Copper

Flashing Red

For more than four years, Dr. Center, a Professor of Internal Medicine at Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine, has led an effort to warn regulators, animal health professionals, consumers, and the news media of excess copper in dog food, conclusion based on decades of peer reviewed research with Labradors and other breeds. In 2019, Dr. Center and fellow board-certified specialists (also known as “ACVIM Diplomates” – read more about ACVIM here) published an ACVIM Consensus Statement. Along with Dr. David C. Twedt, a Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) and Professor Emeritus at Colorado State University’s Dept. of Clinical Sciences, and other colleagues, Dr. Center’s findings indicate more copper in dog food and more dogs are suffering from copper associated hepatopathy (CAH).

“Those of us that have been treating liver disease for 30, 40 years, we see a problem,” Dr. Twedt told The Canine Review in a recent interview.

We have animals that are dying, and we also have clients that are spending a tremendous amount of money.”

Regulators Stall at August 1, 2023 Meeting

As noted, on August 1, AAFCO held another meeting which TCR attended virtually. A debate occurred over how or whether to allow pet food manufacturers to offer products with a low copper content label. The largest trade group representing pet food companies, the Pet Food Institute (PFI), was making a case for inaction.

Dr. Marcy Campion, who works for the Cargill Pet Field Pet Food Division and as a representative of the PFI gave her position.

“We need to make sure we have science-based data before we move too much further into this,” she said. “The PFI is strongly opposed to marketing and selling low copper dog foods in retail channels, rather than containing it within veterinary clinics and channels only… allowing these types of products in the retail market may be misleading to the pet parents who may make assumptions that the copper levels and other types of diets that don’t contain this claim are known to be harmful, which at this point, we don’t know that to be true.”

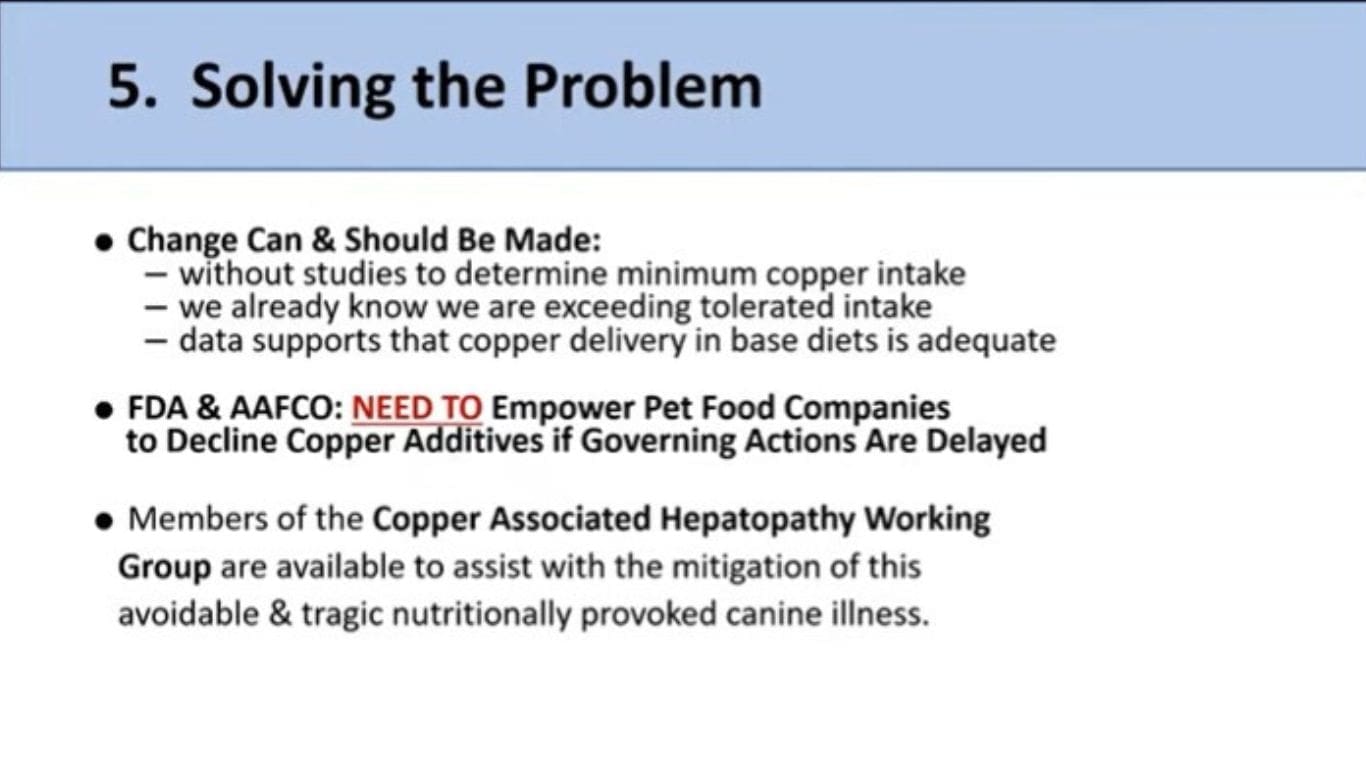

Even if the industry yielded, pet food companies cannot change protocols without the FDA and AAFCO taking the lead, Dr. Center explained in a Sept. 2021 FDA Virtual Listening Session on Pet Food Oversight.

“Members of the Copper Associated Hepatopathy Working Group are available to assist with the mitigation of this avoidable and tragic nutritionally provoked canine illness,” Dr. Center concluded at the presentation.

…avoidable and tragic nutritionally provoked canine illness.”

However, at the August 1 meeting, AAFCO experts and pet food reps didn’t reach any resolutions about next steps, instead calling for “more research.”

How Copper Became a Problem

Dogs absorb copper through diet, and then briefly store it in the liver where it is excreted as bile— a natural function of a dog’s endocrine system. Copper becomes an issue when a buildup in the liver occurs, which can eventually cause disease, brain damage, and liver failure.

Many foods, such as sweet potatoes, contain miniscule quantities of copper. There are larger amounts in other foods, like fish and livers from other animals. And the amount of copper absorption and storage in dogs can be influenced by other factors in diet, including other minerals such as zinc, and fiber, according to Dr. Center.

“In the 1930s and thereabout, copper content in dogs’ [livers] was about 50 to 75 parts per million [micrograms per gram] dry weight, and that’s the same amount identified in people,” Dr. Twedt told TCR. “Over the years,” he continued, “we’ve identified that normal copper levels have steadily increased to today where values are in the range of 400 micrograms per gram dry weight,” he said. “That’s a significant increase. And the question is, why do we see that increase?”

“Certainly, there are likely some genetic aspects, but I think diet also has to play a role,” he added.

In 2007, AAFCO removed its 250 mg Cu/kg DM upper limit. Because mineral premixes are added to most commercial dog foods to meet FDA’s minimum copper guideline, the average amount of copper in food is currently between 20 to 30 mg Cu/kg DM. Even that amount, fed over a lifetime, is high enough to make dogs sick, according to Dr. Center.

“From work done in Labrador Retrievers, feeding a diet delivering [approximately] 7 mg Cu/kg DM diet does not culminate [to CAH],” said Dr. Center in a statement to TCR. “We also know that this level is safe for dogs of any breed treated for CAH as a lifetime prevention strategy.”

After losing his own dog to copper liver disease, one veterinarian decided to get into the dog food business.

“She became cirrhotic…”

“[Cookie]had so much copper in her that, for such a period of time, she had become cirrhotic. And when she became cirrhotic, she had come to the point of no return,” Dr. Philip “Pete” VanVranken told TCR.

“I didn’t realize she’d lost eight pounds,” Dr. VanVranken said about his family’s mixed breed dog Cookie. “And by the time she started doing the vomiting and stuff, I took her in, and she had elevated liver enzymes…She had 2,200 parts per million of copper,” he added, referring to the results of his dying dog’s liver biopsy.

After another month of fighting for his dog, Dr. VanVranken euthanized Cookie. “I knew what had happened and why it had happened,” he told TCR. He subsequently called the manufacturer of the food his dog had been eating, which he identified as Hill’s Science Diet. Hill’s Science Diet does not provide the amount of copper on its dog food labels, nor does it give that information to the public, it can only be acquired through a veterinarian. He said when he called the company to report what had occurred with Cookie, he ended up getting “lip service.”

To supply his other five dogs with a balanced meal—one in which he determined the amount of every ingredient—he started The Scoop, his low copper dog food brand, with just barely over the regulated minimum of cooper and no added mineral premixes.

"Sufficient evidence does not yet exist" ?

“Sufficient evidence does not yet exist to thoughtfully establish a maximum that’s appropriate for all canines,” Anne Norris told TCR by email. No individual at the FDA would agree to be interviewed for this story, and Center for Veterinary Medicine Director Tracey Forfa declined multiple requests seeking comment when asked if consumers should regard the FDA’s position as a rejection of the science Dr. Center and her colleagues have closely adhered to and presented to so many veterinary colleagues.

“It would have been encouraging to see the FDA appoint real experts in the diagnosis and management of canine liver disease and individuals engaged in research to the expert panel discussing this issue,” said Dr. Center.

“Real experts in this area should be engaging with AAFCO personnel that seemingly play an influential role in the decision-making process.”

Dr. Center and her colleagues said the FDA’s position is illogical, as is the implication that researchers should give dogs lethal doses of copper to provide enough data to change its position on establishing a maximum.

“AAFCO actually wanted us to come up with a value for toxicity and to publish that because they say there’s no published data,” she said. “Well, we can’t do that. We think there’s enough of our collective clinical experience to be able to say that we’re just putting too much in and clients are suffering, and the dogs are suffering.”

In 2019, the European Union set a copper maximum for dog food at 25 mg Cu/kg DM and that number is incorporated in the European Pet Food Industry Federation nutrient guidelines.

Dr. Center, Dr. Twedt, and other veterinary internists are imploring AAFCO and the FDA set the copper maximum at 15 mg Cu/kg DM, because dogs with genetic predispositions such as Labs have shown clinical signs with a diet of more than 15. The vets also call for clearer labeling of copper.

“There is no labeling declaration of baseline diet copper content, specific premix used, or its copper content, or most importantly, the total marketed diet copper content [in the form of (mg copper/kg DM)],” she said. “The explanation offered as to why baseline dietary copper content is not routinely measured before premix supplementation is that dietary ingredients shift with market availability.”

"They’re mad as hell."

Dr. VanVranken said his experience with Cookie made him more plain-spoken about what he sees as a pervasive problem for animal health.

“I talk to somebody every week whose dog had copper storage disease,” he said. “You know what they are? They’re disappointed and they’re mad, and they aren’t just mad. They’re mad as hell.”

The pet food industry stakeholders who attend regulatory meetings have been less than receptive to the science. The August 1 AAFCO meeting to discuss the panel’s recommendation of a voluntary “low copper” label was stalled by industy concerns the conversation included how to provide dog owners with a food’s copper content on its packaging. No conclusion was reached.

“None of the information that was shared during last week’s pet food committee meeting changes the recommendations that were included in the copper expert panel report,” said AAFCO CEO Austin Therrell in a statement to TCR. “There’s still not enough data to support a maximum copper level, as evidenced by multiple experts that all had different opinions at this meeting. The only item moving along for discussion is forming a new workgroup that will explore the development of voluntary language for ‘low copper claims.’”

It’s Looney Tunes. This is the part for me that’s so hard to understand,” Dr. VanVranken said when asked why copper minimums were put in place to begin with.”

Dr. VanVranken is referring to the industry’s established copper minimum of 7.3 mg Cu/kg DM, which he and renowned experts like Dr. Center contend is based on a study was not useful because it used growing puppies, so it’s not applicable to adult dogs.

When asked about the need for a copper minimum given the study Dr. Center and her colleagues point to as meaningless, FDA spokesperson Anne Norris disagreed. “Copper deficiency in dogs is not common, but it can happen,” she said by email.

Like Dr. VanVranken, Dr. Center also finds the idea of copper deficiency in dogs absurd. “Nevertheless, and despite the fact that there had been no evidence of widespread clinical copper deficiency in dogs prior to this study, recommendations for dietary sources of copper were subsequently modified,” Dr. Center wrote with her colleagues in the February 2021 JAVMA article.

Calling All Pet Food Companies

Pet food companies operating in the United States are under no obligation to disclose the amount of copper (milligrams per kilogram) on the labeling or packaging of products. But a company may volunteer to provide the information to consumers. And many companies do provide the information, as we learned from a dog owner who set out to solve the problem on her own by calling pet food companies herself.

“We recommend consumers contact pet food manufacturers for information on copper levels if they are concerned with copper intake,” FDA spokesperson Anne Norris said in an email. In follow-up inquiries with the FDA’s Director of the Center for Veterinary Medicine Tracey Forfa, when asked why a consumer should be required to call pet food companies themselves for key information needed to assess the safety of pet food, Director Forfa did not respond.

Not every industry stakeholder is opposed to label requirements. Dr. David A. Dzanis is a board-certified veterinary nutritionist who regularly consults for pet food companies. “We’ve run into this problem before, having to call up every pet food company and say, ‘What’s your copper level of this diet?’ And each company has a dozen or more varieties,” Dr. Dave Dzanis said at the August 1 AAFCO pet food meeting. Dr. Dzanis was also a consultant for the copper expert panel making recommendations for AAFCO.

“And to do that company after company, after company. And each individual would have to do that is a tremendous burden on the consumer, compared to just having that information available,” he said. “It’s statement of fact on the label, and I’d much rather have some guidance as to under what circumstances they can provide that information rather than not.”

The High Price of Diagnosing Copper Liver Disease

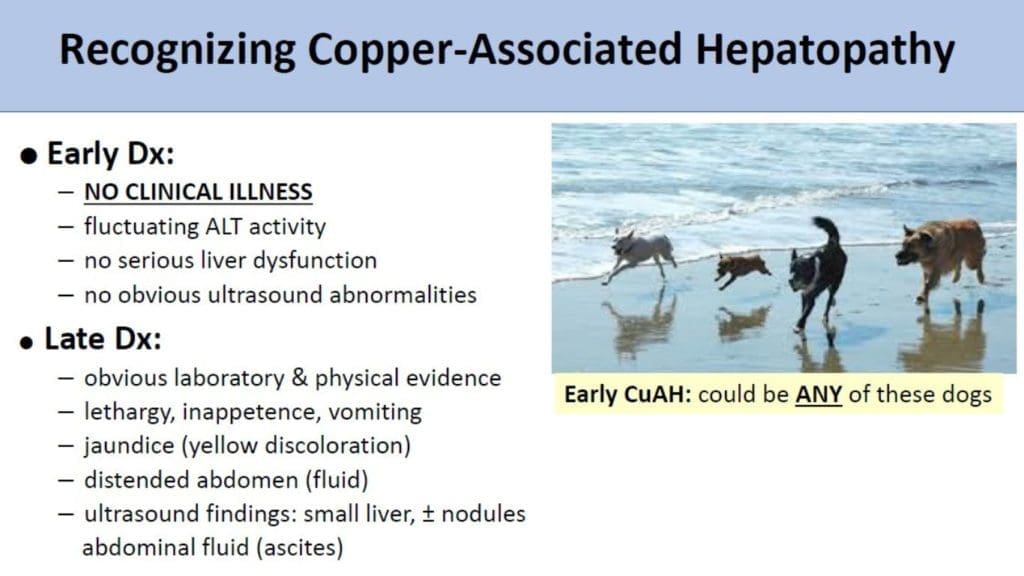

CAH is difficult to catch early. As Dr. Center notes, in the early stages of the disease, there are often no clinical signs. It is not until later in the disease progression that it becomes detectable in diagnostics such as ALT level (bloodwork), symptoms such as lethargy, vomitting , and inappetence.

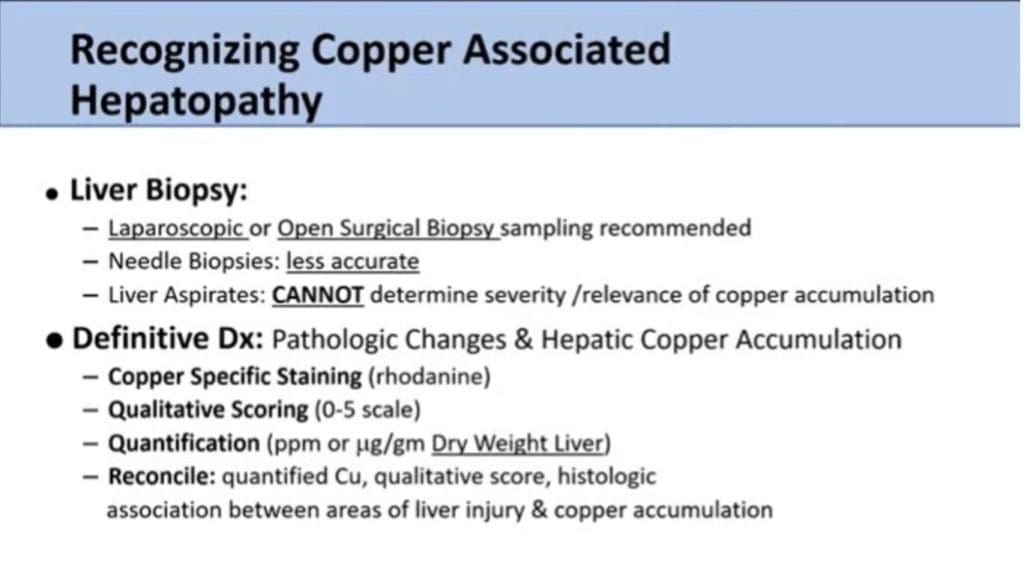

A diagnosis requires a liver biopsy, which is out of reach for a large population of pet owners due to cost, which, in Manhattan, would be at least $5,000.

“Besides the pain and suffering that these dogs experience the cost of diagnosis and treatment…ranges from $4,000 to $15,000 depending on the severity of copper accumulation, the time needed for chelation treatment (removal of copper from the liver) and a lifetime commitment to the feeding of a copper restricted diet,” said Dr. Center. “Sadly, the expense of diagnosis and treatment is beyond the means of some dog owners, leaving the dog…with the potential for eventual liver failure or a decision for humane euthanasia.”

ANY of these dogs,” Dr. Center explained in the 2021 presentation could be in the early stages of the disease.

“You have to look at what is going on in the liver, and that requires a liver biopsy,” Dr. Twedt told TCR. “And that’s very expensive and somewhat invasive.”

“However,” he said, “I’m a big advocate of routine health checks and preventative medicine. And if one were to identify that their dog has abnormal liver enzymes that are unexplained, those are the animals that should have their liver investigated.”

Yet most dogs with copper storage diseases never get diagnosed.

“I think the fact that only one out of every 20 cases are diagnosed tells you almost everything you need to know,” Dr. VanVranken said about regulators’ reluctance to establish a copper maximum.

“The nutritional amount of copper in a dog’s diet is a complex issue and is best discussed by dog owners with their veterinarian,” FDA spokesperson Anne Norris said.

What should dog owners do?

Simply put, pet food companies are not currently regulated in a way that requires comprehensive disclosures to consumers when a company becomes aware of a key safety concern pertaining to ingredients, even if the person sounding the alarm is Cornell’s Dr. Center. There are also limited resources for consumers who want more information about pet food, including how much copper a product contains.

“Because we just do not know who will be affected, a safe approach is to use a copper restricted, but not a protein restricted liver diet,” Dr. Center said. Only a few brands, including Royal Canin and The Scoop, offer “low copper” dog food brands without a prescription.

Dr. Center, Dr. Twedt, and the other “Viewpoint” authors urge colleagues to encourage clients who own dogs diagnosed with copper hepatopathy to report it to the FDA.

“I think what has to happen is AAFCO needs to reconsider what they’re doing as far as diets,” Dr. Twedt said, “and then make those recommendations to the FDA and [that] all the commercial dog food companies follow AAFCO guidelines.

Follow the prompts after clicking this link to the FDA’s pet food complaint questionnaire: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/report-problem/how-report-pet-food-complaint. In addition, consider contacting news organizations. Reach out to your local newspaper. You can reach out to TCR at editor@thecaninereview.com

Follow the prompts after clicking this link to the FDA’s pet food complaint questionnaire: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/report-problem/how-report-pet-food-complaint. In addition, consider contacting news organizations. Reach out to your local newspaper. You can reach out to TCR at editor@thecaninereview.com

RELATED:

The owner of a Labrador retriever with liver disease searches for her own answers