Top Vet Hospitals Cope With Covid

TOP VET HOSPITALS COPE WITH COVID PPE, Money Challenges; Telemedicine Opportunities

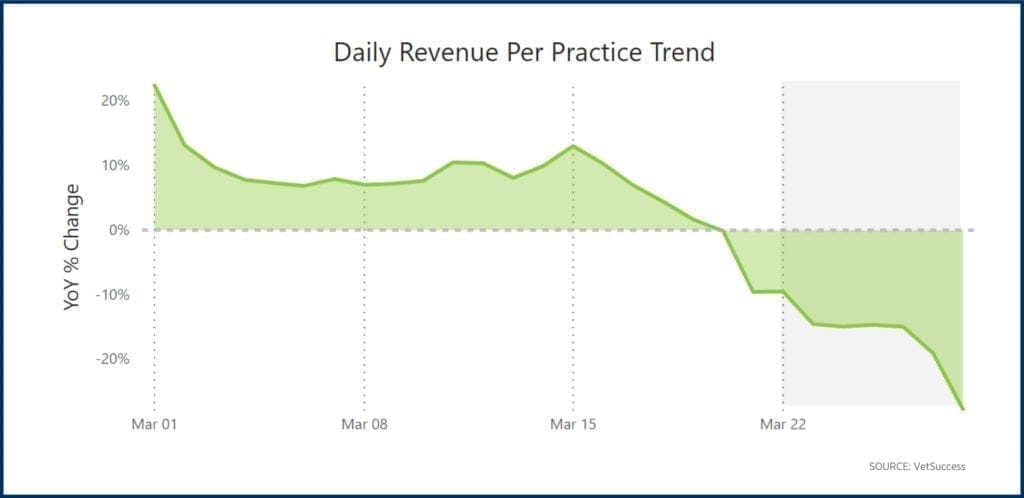

Like so much of the economy, America’s $29.3 billion veterinary industry was turned upside down this spring as full-scale lockdown orders on businesses deemed non-essential, along with stringent physical distancing rules and guidelines, swept the nation. Most states and localities identified veterinary practitioners as essential workers. Therefore, they were exempt from lockdown restrictions. However, although veterinary practices have mostly remained open throughout the pandemic, the industry has reported substantial losses in revenue during March and April and through early May.

The decline in clients willing to brave the shutdown to seek care for their pets was exacerbated by the global scramble for personal protective equipment in a time of unprecedented manufacturing shortages. This left many veterinary practices with ongoing equipment shortages, forcing these practices to cancel or postpone non-urgent care to conserve items like gowns.

Now, about three months since the first confirmed Covid-19 death on U.S. soil, most of the country’s jurisdictions have begun to lift restrictions and reopen. The Canine Review spoke with five of the world’s most renowned 24-hour veterinary specialty hospitals about how they have navigated challenges posed by the pandemic and how they are moving forward as America heads into summer and reopens against a backdrop of economic recession, 100,000 plus virus-related deaths, historic unemployment, state and city budget deficits, violent police protests, and so much uncertainty.

Angell Animal Medical Center Boston, MA

In Massachusetts — where, according to the New York Times, about 800 new COVID-19 cases each day continue to be reported and where 6,640 people have died from causes related to the virus — Angell Animal Medical Center in Boston is one of the country’s oldest and most renowned veterinary hospitals. Now part of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty for Animals (MSPCA), Angell celebrated its centennial in 2015; The Boston Globe marked the occasion with a 13-page cover spread in its magazine.

When Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker ordered nonessential businesses to cease in-person operations starting March 24, Angell “pretty much immediately” stopped allowing clients inside the building and asked almost all administrative employees to work remotely, Angell’s Dr. Virginia Sinnott-Stutzman, chair of the Infection Control Committee, explained in an interview.

‘Gowns are the worst.’

Surgical gowns have been the most challenging type of personal protective equipment for the hospital to procure since the first weeks of the pandemic. “Gowns are the worst,” Sinnott-Stutzman said. “We really are having a hard time finding reusable gowns…I think we’re down to like 100, which seems like a lot until you realize we employ, you know, 120 veterinarians, let alone however many techs that go along with that.”

Dr. Sinnott-Stutzman, who is board-certified in Emergency and Critical Care, said that masks have been easier to procure because volunteers who normally walk dogs at the animal shelter attached to the hospital have instead been “sewing masks like crazy.” Also, there has been a steady flow of donated masks from the public. Sinnott-Stutzman added that the hospital had a small but adequate supply of surgical masks, which they limit for uses such as orthopedic surgery, when, she explained, “there’s going to be an implant like a plate because the chances for an infection or the consequences of an infection are much higher with an implant.. If your plate gets infected, it has to come out…”

‘Those dogs are lame but they’re not going to die.’

Not much orthopedic surgery was taking place, however, for the first 4-6 weeks of the lockdown. “We suspended knee surgeries, like TPLO’s, so those dogs are lame but they’re not going to die,” Sinnott-Stutzman said. Spays and neuters were also postponed. Other surgeries and visits deemed as non-urgent were rescheduled. The hospital has started performing elective surgeries again, but not at the same volume. “We don’t overwhelm the surgery service and consume lots of PPE,” she explained. “We might have done twelve to sixteen knee surgeries a week and… I think each surgeon is limited to one or two, so that’s…five to ten.”

‘Significantly Impacted’

Asked about the pandemic’s financial impact on the hospital and how ongoing limits on services such as knee surgeries factored, hospital spokesman Rob Halpin wrote in an email, “We don’t disclose the specific financial details related to the pandemic’s impact on Angell Animal Medical Center. But we can tell you that limiting our services to urgent and emergent care has, over the last three months, significantly impacted Angell’s bottom line. We do not anticipate having to make notable changes to the operating budget, however,” Halpin added.

Dr. Sinnott-Stutzman was enthusiastic about telemedicine, for reasons beyond its obvious convenience: “You might not get the same information in terms of putting your hands on the pet,” she explained, “But man, you get some different and very good information. Like, seeing the pet in their home environment and how they’re behaving like, are they curled up in the corner in the home environment looking sad? I can’t tell you how many clients tell me, you know, with their dog jumping around the waiting room, how sick the dog looked at home, but seeing it in the video is really helpful to go, ‘Oh I see what you’re saying…..Sometimes it might be in some cases better information…”

‘I would feel like the worst human in the world.’

Although Angell has struggled to maintain adequate supply levels of personal protective equipment since the early weeks of the pandemic, the hospital nonetheless donated many of its coveted supplies to neighboring human hospitals, along with its only ventilator. “We donated our ventilator,” Sinnott-Stutzman said. “They only had it for about a month and half….There was maybe one case of many, many respiratory cases that we saw during Covid where I felt like the dog would’ve had a better shot with a ventilator, but it happened to be right when we locked down and the owners were like, ‘If you were ventilating my dog right now, I would feel like the worst human in the world.’ Because we were at that surge and people were dying for lack of ventilators…It was really–Boston got pretty–We weren’t as bad as New York by any stretch of the imagination, but when we were at our surge, we were at something like 90% of our hospital capacity.”

“The other big piece with ventilation,” she continued, “is that it’s very labor intensive.” Sinnott-Stutzman explained that another reason the hospital decided to donate its ventilator was because, “We may not have been able to have the staffing to ventilate… we were like, ‘we may not even be able to physically use the machine.’”

‘Construction Actually Starts Next Month’

Asked if the crunch has caused any changes in plans as far as major projects, Sinnott-Stutzman said that everything was proceeding as planned, including plans to expand the hospital’s ICU. “So, construction actually starts next month, which is so weird to me, but yeah, we’re doing it! Weird only because, like, who’s doing construction during the pandemic?”

The Animal Medical Center New York, NY

There is at least one other world-renowned veterinary hospital with major construction plans for 2020: The Animal Medical Center in midtown Manhattan.

The world’s largest veterinary nonprofit teaching hospital with clients coming from as far as France and 35 states within the U.S., the Animal Medical Center (AMC) is a New York institution, its East 62nd street location a football throw from some of the world’s leading human hospitals that have been engulfed in a Coronavirus battleground.

Declared America’s Covid-19 epicenter, New York City is one of the few places that today remains under a full lockdown order. Like most veterinary hospitals, AMC instituted ‘curbside check-in’ protocols; clients have not been permitted inside the building since mid-March. To conserve personal protective equipment and support physical distancing, AMC significantly reduced the number of employees working inside the building and postponed non-urgent visits and services not considered “essential care.”

In a statement provided to The Canine Review through hospital spokesperson Barbara Ross, Chief Executive Officer Kathryn Coyne wrote, “As an essential business, AMC has remained open for the people and pets of New York City throughout COVID-19. We immediately set to work, overcoming many obstacles to comply with New York State’s shelter-in-place policies and deliver the highest quality emergent and critical care veterinary services. Within two weeks, and with guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and New York City and New York State Health Departments, AMC quickly adapted to new measures, procedures, and protocols to safeguard our staff, our clients, our patients, and our facility against COVID-19. We restricted public access to the building, installed heated, outdoor client waiting areas, maintain all client communication through phone and email, and established separate hotline numbers (one for clients; another for referring veterinarians) to call with questions to help determine if an animal should be sent to the ER.”

‘Constantly Working to Ensure Our Staff Have PPE’

Asked about personal protective equipment supply levels, Ms. Coyne wrote, “We are constantly working to ensure our staff have PPE, and we were fortunate to receive a generous donation of KN-95 masks and surgical masks from the BStrong Foundation in partnership with the Global Empowerment Mission.”

‘Capital Campaign Is Still Underway’

Last fall, the hospital unveiled a $70 million capital campaign to renovate its 60-year-old building. Construction was “set to begin in Spring 2020,” according to a hospital press release. Asked about the status of those renovation plans, Ms. Coyne wrote, “The capital campaign is still underway; however, the timeline will of course be determined by how and when the city reopens.”

‘Tremendous Impact’

Like Angell, AMC would not comment specifically about the pandemic’s financial impact. However, in an email to hospital donors announcing a newly established Covid-19 Emergency Fund in early April, Coyne wrote, “The impact on AMC has been tremendous, and it is not only operational – requiring us to establish protocols to protect the health and well-being of our staff and clientele – but financial. We currently project a cumulative loss of $7.5 million in income by the end of 2020…AMC’s management team and Board of Trustees are actively taking steps to alleviate the shortfall in revenue. We are making difficult, but necessary adjustments to AMC’s operating budget and to our daily operations. In addition, we are evaluating our investments and seeking government assistance.”

Despite the many challenges the hospital has been faced with this spring, AMC donated five much-needed ventilators to neighboring hospital New York Presbyterian, along with PPE to other nearby hospitals. “Our medical team stands in solidarity with our colleagues in human medicine,” Ms. Coyne wrote.

At the Animal Medical Center, we’re proud to support our human health counterparts in their fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yesterday, we donated our ventilator to @nyphospital so it can be used in their valiant, lifesaving work. pic.twitter.com/Op5T4iodAe— Animal Medical Center (@amcny) March 27, 2020

“Yesterday, we donated our ventilator to NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital,” the hospital wrote on its social media platforms to great fanfare in late March, “so it can be used in their valiant, lifesaving work. And in the coming days, we will be sending PPE to other local hospitals. It’s in times of great crisis that New Yorkers step up for each other like no other, and as a New York institution, we’ll continue doing everything we can for our clients, patients, and community. AMC has a long-standing commitment to One Health – the unbreakable connection between human and animal medicine – and today, as always, we stand in solidarity with our colleagues in human medicine.”

UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital Davis, CA

About 75 miles from San Francisco and 15 miles from Sacramento, the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine is consistently ranked the #1 veterinary school in the country by U.S. News & World Report. Its veterinary teaching hospital is world-renowned. Among other distinctions, the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH) helped pioneer dialysis treatments for companion animals. The hospital’s specialty services for small animals include Genetics, Theriogenology (reproduction and fertility), Nutrition, Hemodialysis, and Behavior.

VMTH has not allowed clients inside its building since March 16, hospital spokesman Rob Warren said in an email, although exceptions are made for end-of-life cases. “During that ‘emergency only’ period, the Veterinary Medicine Teaching Hospital utilized curbside check-in with clients remaining in their vehicles,” Warren said in an email to The Canine Review. “After the May 13 phased re-opening, the VMTH has initiated an outdoor check-in booth and a temporary waiting room in a vacant campus site that allows for proper social distancing.” According to Warren, the hospital remained open for emergent and critical care. Some non-urgent specialty services have now resumed, starting with clients wishing to reschedule appointments that had been postponed. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, rechecks for animals with certain medical conditions have taken place at VMTH through telemedicine, according to Warren.

The hospital declined to answer questions about personal protective equipment supply levels, but Warren said that the hospital had six ventilators which they were prepared to loan to the UC Davis Medical Center upon request. However, the need never arose, according to Warren.

Even with funding for businesses in jeopardy across the country, many veterinary specialty hospitals like VMTH were able to proceed with construction projects already underway. Funding for two projects–a remodel of laundry facilities and the construction of a feline-exclusive hospitalization ward- had already been secured prior to the start of the pandemic, Warren said. With 90% less people in the VMTH facility, the construction team was able to work more efficiently toward completion, according to Warren.

Washington State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital Pullman, WA

The Washington State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Pullman is nearly five hours from where America had its first confirmed case of Coronavirus. Nonetheless, spokesman Charlie Powell says the hospital implemented several significant changes to conserve personal protective equipment and minimize the risk of infection. “We shut the hospital down to clients coming in the door,” said Powell. “We were still taking emergency and critical care patients in, but the owners had to wait outside. The animals were received outside the doors.”

‘All reverses itself on June 8’

Wellness visits and elective procedures such as dental cleanings continue to be on hold; Powell says that they will not be back on the schedule until June 8. Veterinary students, who typically assist with these procedures, were dismissed for the remainder of the year in March. “Our workforce in the teaching hospital, as well as our teaching load, was simultaneously lowered as a result,” said Powell. “But that all reverses itself on June 8.”

Powell predicts that telemedicine will continue to be practiced even when the pandemic winds down. “We have seen the value of it,” he said. “And it works fairly well. I would imagine there would be more telemedicine occurring and most of that is a result of veterinary licensing boards loosening their restriction on that. I think telemedicine is going to be a force multiplier to use for clinical care.”

Powell said the VTH never encountered any shortages of personal protective equipment. Powell explained, “We had more than enough PPE because we laid in an extra supply anticipating this was going to occur. So, when the shutdown hit, our supplies were greater than capacity.” Supplies of drugs such as propofol remained in good supply, he added, “But we do have on-going supply issues with IV solutions in large quantities, particularly for our equine section. But that was occurring long before COVID-19 came along.”

However, in a media release issued by Powell on April 3, the hospital’s supply levels appear to be more precarious than, perhaps, Powell in short supply of some types of personal protective equipment: WSU VETERINARY TEACHING HOSPITAL ALSO NEEDS CLOTH MASKS:

As for construction and other big projects, some projects were suspended due to the pandemic, but others continued, Powell said. The VTH’s diagnostic laboratory has a $65 million project underway and construction was deemed essential during the pandemic.

With regard to increased liability concerns, Powell said the hospital is regularly entangled in lawsuits and COVID-19 does not worry him as a liability issue, particularly as it relates to clients. “We don’t see any lawsuits related to COVID-19 from clients,” said Powell. Employees, however, appear to be of some concern. “Some employees are segregating into two camps: one who don’t want to use PPE because they think this is all fake and the other camp that says they need every piece of PPE known to man and I will wear all day, every day and use it once. Both of those are camps that are quite vocal. We hope it will get smoothed out through peer pressure as we open the hospital and most of their peers are using appropriate distancing and those kinds of things. But I do think in a hospital of 200+ employees, there’s bound to be one or two that are extraordinarily upset and choose to move on or threaten litigation.”

Gulf Coast Veterinary Specialists Houston, Texas

At Gulf Coast Veterinary Specialists in Houston, Texas, Hospital Director Brian Harnish says that the only item the hospital ran out of during Covid-19 was canned chicken. “It [the virus] hit home for Houston on March 11. And, I have that specific date,” Harnish explained, “because at the time, the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo was going on and that’s a very big event here in Houston.” [On March 11, the Houston Rodeo Show was cancelled because of coronavirus.]

It was, perhaps, the hospital’s extensive, hands-on experience with emergency and disaster that made GCVS appear to be the most well-prepared of all of the hospitals we spoke with. In August 2017, GCVS “crumbled and fell into a bayou” during Hurricane Harvey, Harnish says. “The last people left the building at 1am in waist deep water.”

Unlike its peers in the northeast, GCVS’s building is less than two years old, so renovation and construction are not on Harnish’s bucket list. Asked about other major expenses or projects, Harnish says, “We did pause some equipment acquisitions, but I emphasize pause.”

Harnish disagrees with Angell’s Dr. Sinnott-Stutzman, who said that in most cases, dogs requiring surgery for cruciate tears (known as TPLO) were not considered urgent cases. “That’s a debated topic throughout veterinary [medicine] as to what’s essential or not… A cruciate ligament tear usually results in a TPLO or some other procedure, and it’s very, very common. And the argument is that it’s non-essential and that it can wait. Agree, it can wait. But what happens when you wait on a TPLO or cruciate tear is that the tear worsens and it makes the repair more difficult…When you take an early onset of a cruciate tear and give it to one of our surgeons, the recovery time is very short because we use minimally invasive procedures…That patient has a very high likelihood to have a 100% recovery in a matter of weeks, and the longer we wait the more difficult that repair is going to be.. so, to say that it’s non-essential I think is misleading.”

Relatedly, Harnish says that no services at GCVS were ever postponed or discontinued, including the availability of mechanical ventilators, which the hospital chose not to donate to human hospitals battling coronavirus. “The other thing we have to our advantage here in Houston is the Texas Medical Center and that’s the largest medical district on the planet and the ninth-largest business district in the world of any kind of business. Within a three-mile stretch of one street, there are 125,000 medical professionals working in the 25 hospitals [which include world-renowned MD Anderson]. They didn’t need our eight ventilators to change the game,” Harnish added.

“I had a perspective,” says Harnish, “of I need to keep my people working, which means I need to keep them supplied with equipment and supplies, so we did quite a few things. For example, we hired someone who was laid off from their job to literally walk around this hospital 40 hours a week and wipe door knobs with disinfectant. Is it psychological in nature? To some extent, yes. But if I prevented one of my doctors from getting coronavirus because someone’s wiping doorknobs, it made the cost of that person well worth it, and to be blunt it was cheap insurance and I helped somebody out in the community. Because my personal philosophy on this is that this is a two-part problem…The first part is the virus itself and as terrible as it is and as deadly as it is and as devastating as its been to humans worldwide, the second part of this virus can have the potential to be just as bad and that is the financial part. And my goal was to keep all of my employees gainfully employed to support the community to the best of our ability and not be an additional burden on the rest of the community.”

Harnish points to those who donated masks to GCVS as an example. “We didn’t take donations of masks, for example. We paid everybody who gave us masks $5 for each one. And I bought 1,000…A lot of people making those masks had lost their primary job and it was our way to help forestall financial collapse for those people,” he explained.

‘This is a relational business.’

Telemedicine has been ‘helpful,’ says Harnish, “with a caveat. I really think there’s a limitation to how far it can go. And it’s partly because of the verbal communication. You know, we can’t ask Fluffy where she’s not feeling well.” Asked if he foresees the return of clients and pets to veterinary waiting rooms, Harnish said, “I think by and large most of it will go back to a personal interface model because this is a relational business and it’s a relational industry. You have to have that contact in order to function. There’s just so many things that are missed through the video that a veterinarian would pick up on.”

In-person visits ‘back online’

In fact, at GCVS, some of the hospital’s clients have already started entering the building again for appointments. “This week, we started bringing the initial visit in the exam room back online,” he said, explaining that clients are screened for risk factors and are required to wear masks.

‘Very good inventory management’

How was GCVS able to continue offering a full menu of services when protective equipment was so scarce? “We have a very good inventory management group here,” Harnish explained. “We normally keep a 30-day par level of everything we use. We have a calculated burn rate. So, they know we use 200 masks a day, and so in order to have 200 masks a day, we need to have 6000 on hand to supply a month…On March 11, our inventory team literally bought an additional two months’ worth [of supplies]… We were at the head of the curve,” he added, “before the shortages came. The only thing that we ran out of during the pandemic was canned chicken.”

“Really, the amount of gratitude and pride that I have for our staff and how they performed is really hard to verbalize. I mean, I have 350 people here and it was incredibly important to me to not have to tell any of them that their job was curtailed or that we were reducing hours or any of those kinds of things and in return, you know, it’s like you do your job, I’ll do mine, and together we’ll get through this…The fact that we’re getting through this intact and with a viable business says a lot for the resiliency and drive of the team and all of the pets we were able to take care of during this pandemic.”