ASPCA's New York City Adoption Center (*updated*)

(Please be sure to read the Editor’s Note that we have added at the bottom of this report.)

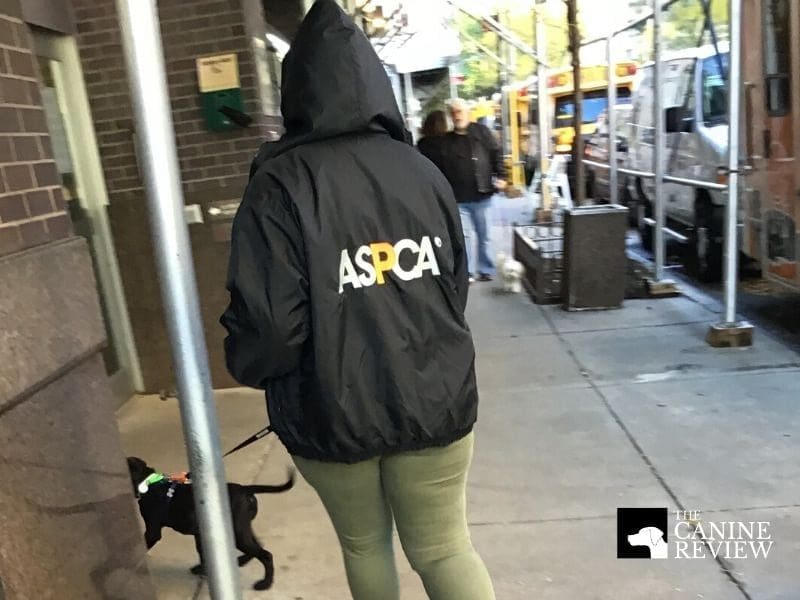

When Amanda, Bernardo, and Sofia Rodriguez walk out of the ASPCA’s Adoption Center on the Upper East Side of Manhattan on a cloudy afternoon in November, their newly adopted four-month-old puppy jumps eagerly beside them. The brown and black puppy’s name is “Sorrento,” “like the cheese,” Amanda tells The Canine Review.

“It was really nice from beginning to end,” Amanda says of the Center’s adoption process. After arriving, the family says they filled out a questionnaire and met with an ASPCA “matchmaker.” The environment was “kid-friendly and we didn’t feel intimidated or pressured at all,” Amanda recalls. Sorrento is a bigger dog than what Amanda says she originally had in mind, but the “matchmaker” thought the dog would be a great fit for her family, she explains. “It was right and I’m thankful because I would’ve never opened up to a dog like this.”

“Every adoption really is a conversation,” says Kelly DiCicco, the ASPCA’s Adoptions Promotions manager, in a phone interview. DiCicco says the ASPCA sends out follow-up surveys three days, three weeks, and three months after an adoption.

Like all dogs who are adopted here, Sorrento came with a “Welcome Home” bag which includes a supply of dog food and a lifetime guaranteed option to return the dog to the shelter if needed. “We always encourage people to really try,” DiCicco says, adding that adopting an animal sometimes requires a transition process.

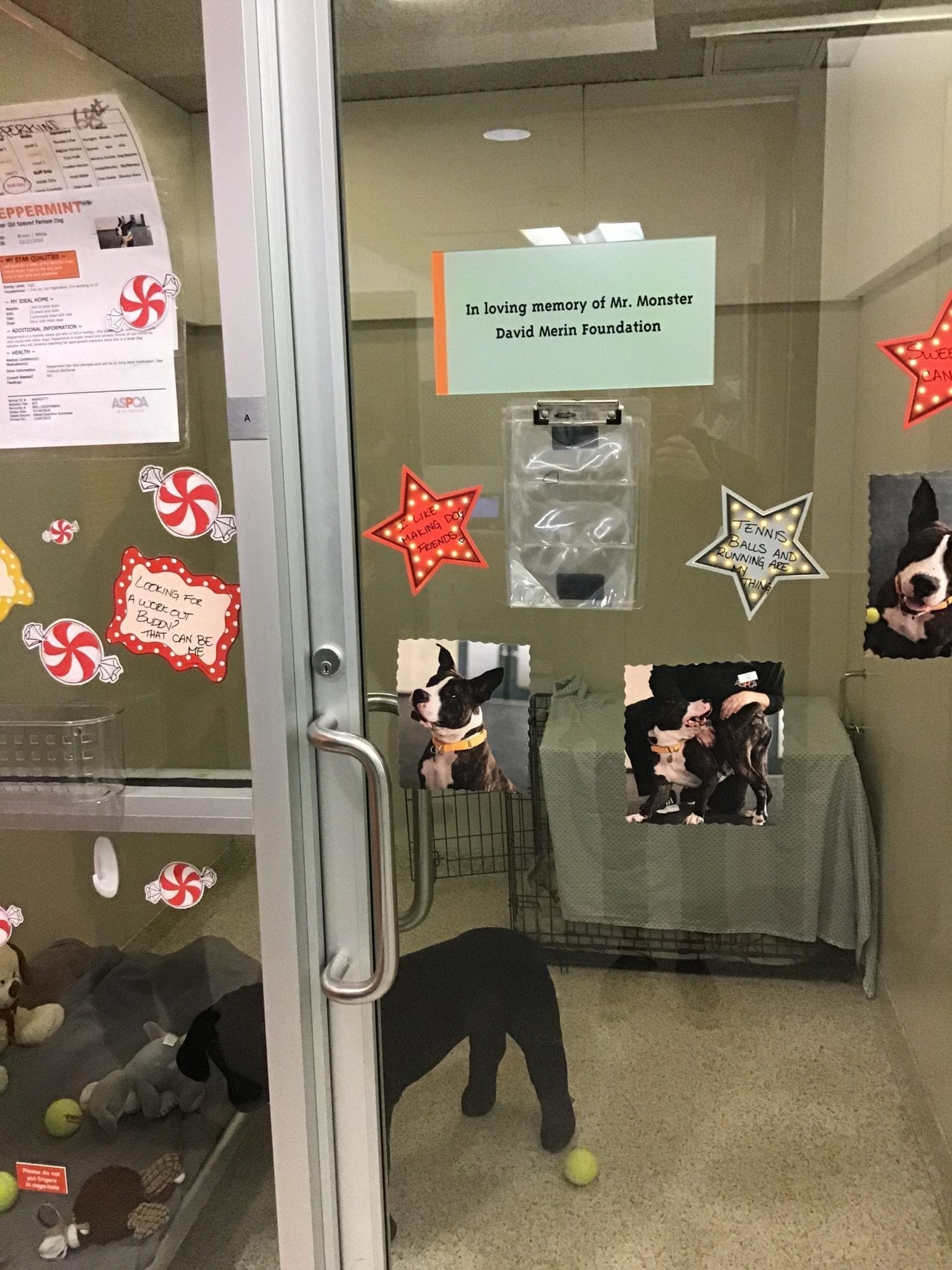

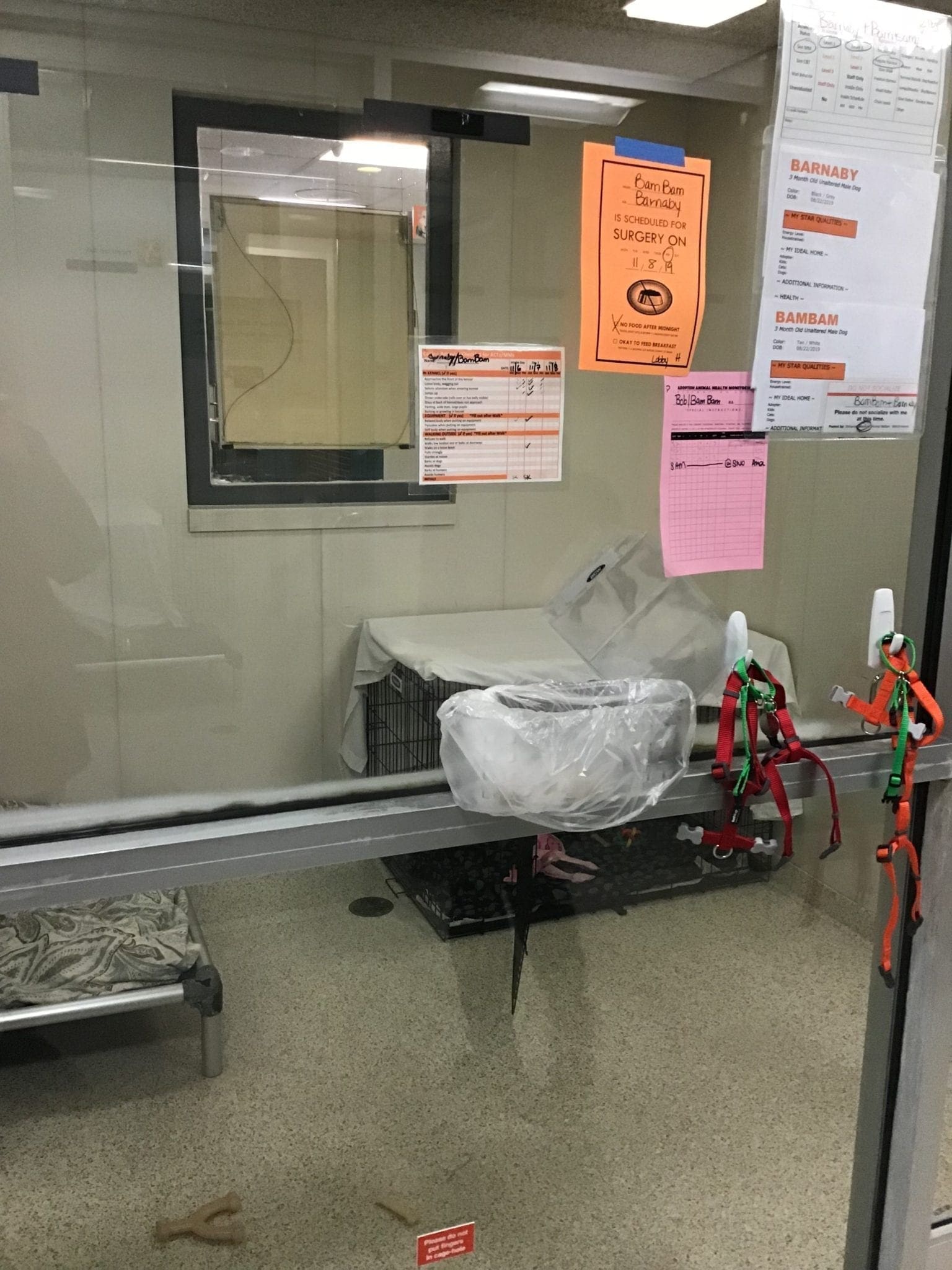

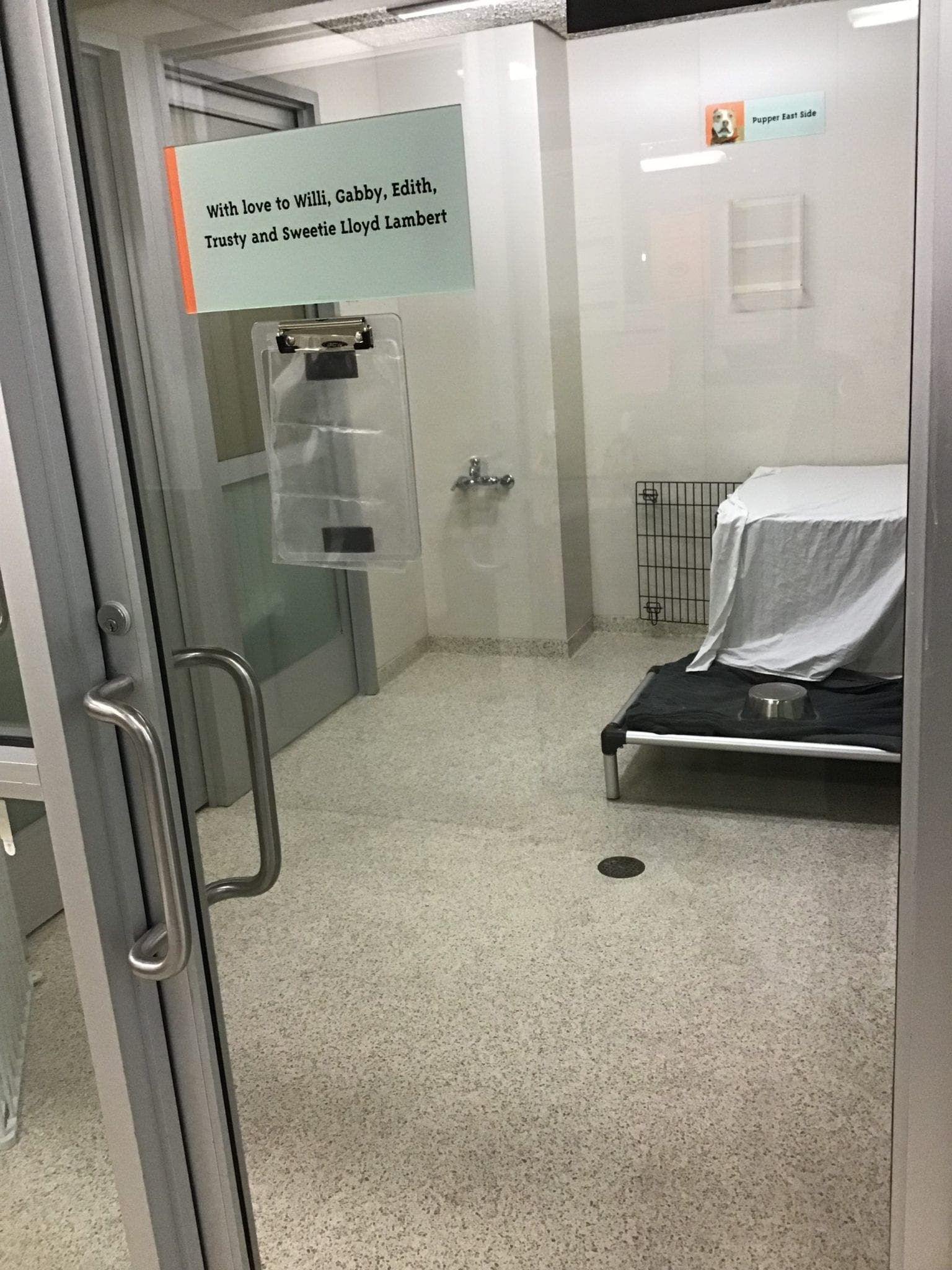

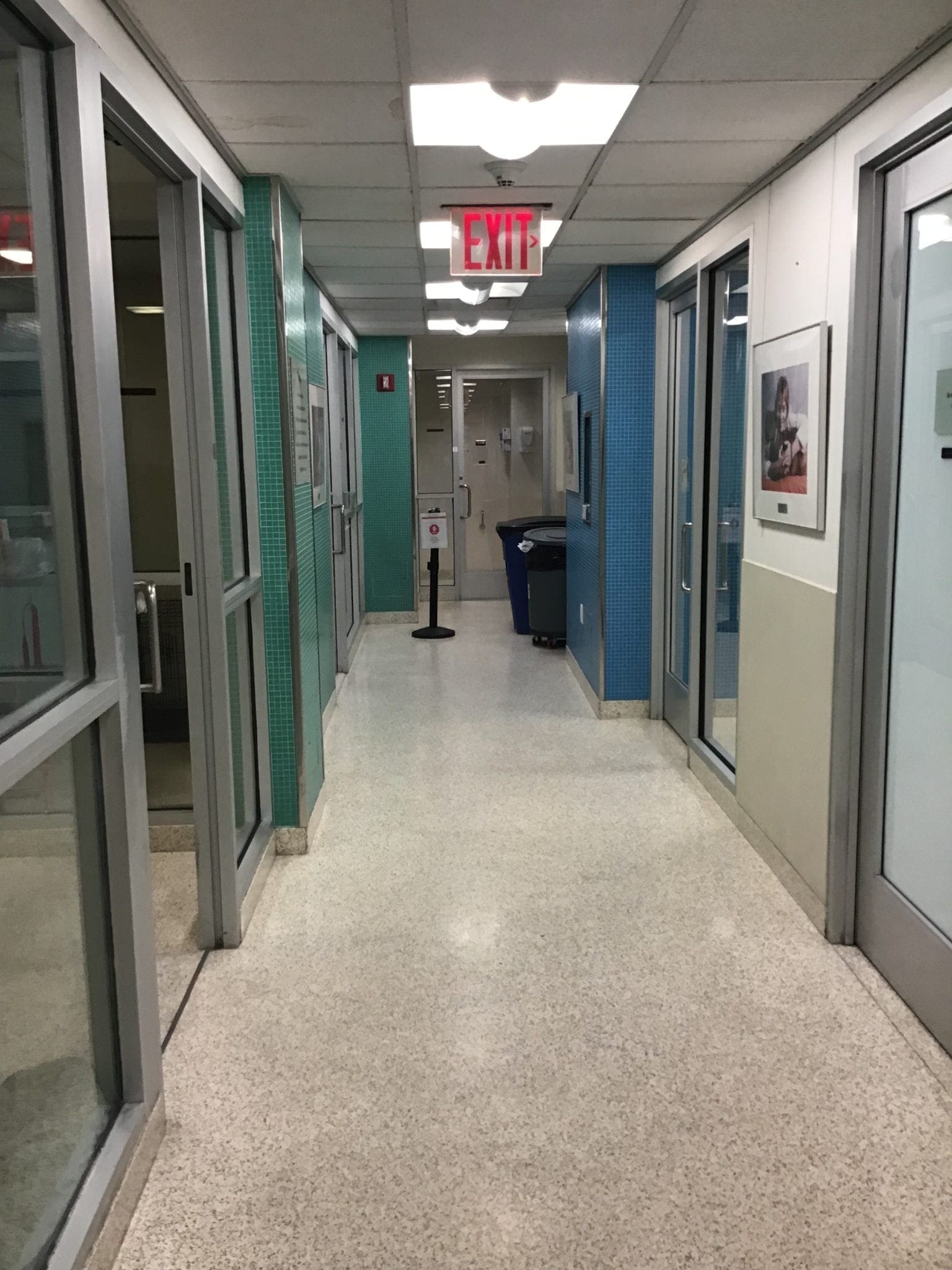

Inside the Adoption Center, families, singles, children, and senior citizens wait to meet their pets. Most of the dogs here live on the first floor in large kennels with at least one glass wall. When The Canine Review visits, almost all of the kennels are empty because the dogs are out on one of their daily walks. The one exception is a kennel where a stuffed dog sits next to an empty bowl of food: The stuffed dog is a stand-in for Peppermint, a two-year old boxer mix. The downstairs kennel environment is too overwhelming for her, so she is upstairs in a quieter space, a shelter employee who did not provide her name explains. The Adoption Center wants to make sure people know that Peppermint is here and available to adopt without putting her in a potentially stressful environment, she adds. Framed photos of people smiling with their already-adopted pets line the walls.

Local SPCA’s and humane societies are not affiliated with the ASPCA. The ASPCA is not affiliated with the SPCA and the East 92nd Street location is the ASPCA’s sole public adoption facility. “The ASPCA also has a number of programs around the country where thousands of additional homeless animals are cared for, treated and placed,” ASPCA spokesman Alexander Craig told The Canine Review.

According to the ASPCA’s 2018 annual report published on its website, the ASPCA has a $260,216,614 overall operating budget. Of that, about $75 million goes towards shelter and veterinary services. The statements do not isolate the NYC Adoption Center’s budget from veterinary services. This is probably because the ASPCA operates both its Adoption Center and Animal Hospital from its NYC Upper East Side location.

ASPCA “has been headquartered in New York City since its founding in 1866 where it maintains a strong local presence,” its 2018 audited financial statement says. “An essential element of our work in NYC that has impact around the country is the ASPCA’s work with the NYPD,” ASPCA spokesman Alexander Craig wrote in a statement to The Canine Review. “We are the only agency in the country that partners with the largest police force to tackle animal cruelty. The learnings from our forensic and legal work with these cases help not only the animals in our care, but other animals and animal welfare organizations around the country.”

The ASPCA has a national presence, too. It operates what it calls a “Behavioral Rehabilitation Center” in North Carolina, where care is provided for animals who have been living in abusive conditions. There is the 24/7 ASPCA Poison Control hotline. ASPCA has community medicine programs in major cities that provide basic, low-cost veterinary care to low-income pet owners. Other programs include humane education and a Farm Animal Welfare department.

ASPCA’s Strong Support, Officially, for Higher Standards for Shelter Data Collection and Transparency – – But Not Transparent With The Shelter It Operates

When The Canine Review first approached the ASPCA’s Manhattan Adoption Center and requested a tour, it was ASPCA spokesman Alexander Craig, whose office is at the ASPCA’s headquarters in midtown, not at the Adoption Center on East 92nd Street, who fielded the request and conducted the tour.

Oddly, though, Mr. Craig insisted that the tour of the ASPCA shelter be “on background.” Both ASPCA President and CEO Matthew Bershadker and Mr. Craig declined to comment when asked why The Canine Review’s tour needed to be “on background.” ASPCA’s NYC shelter is the only animal shelter to date that TCR has profiled that has made ground rules for a tour of its facility.

Moreover, it took several weeks of follow-up requests to Mr. Craig and, finally, to CEO Bershadker, for the organization to agree to provide basic intake and outcome data for 2017, 2018, and 2019.

The ASPCA’s initial reticence was surprising because the organization takes a strong position on its website championing higher standards for shelter data collection and transparency. In its “About Us” section [https://www.aspca.org/about-us/aspca-policy-and-position-statements/position-statement-data-collection-reporting] the ASPCA declares that the Asilomar Accords — a 2004 commitment from animal welfare leaders across the country to standardize its definitions and methods for evaluating animal shelters, and to which ASPCA was a founding signatory — are “inadequate” and “unacceptable.” The ASPCA, therefore, came up with its own, more narrowly defined set of definitions for shelter data, it further explains. ASPCA does “not use several of the Asilomar Accord measures,” in its reports because “the definitions and formulas for the Accords are inadequate for an epidemiological approach” due to the lack of definitional clarity of certain terms including “treatable” and “unhealthy.”

Instead, the ASPCA says in its position paper that it favors drilling down for “hard data” in the following categories: “All Live Intake (including stray, owner relinquish and transfer), Adoptions, Return-to-Owner, Return to Field (for free roaming cats), Transfers, Euthanasia (owner requested and all other), TNR and other Targeted S/N.” Yet, with no hint of irony, the ASPCA does not publish or readily provide any of this data about the shelter it operates.

Just before press time, Mr. Craig wrote in a statement, in part:

The volume and scope of animals that we care for are also unique. Many of the animals in our care are the hardest to place and most complicated to rehabilitate, especially in an urban environment – and we often cannot control or anticipate the number of animals that are brought to our adoption center as a result of urgent cruelty or neglect cases….As we have shared with you previously, the ASPCA Adoption Center supports the most at-risk animal populations, many of which have challenging and complex behavioral and medical needs and require extra care and treatment before being made available for adoption. We don’t use no-kill language. We save as many lives as possible. Our productive relationship with Animal Care Centers of NYC is one element of our overall work. Together we also work with hundreds of smaller animal welfare agencies and rescues to create and sustain a comprehensive and effective animal care program in New York City. Another reason why it is not appropriate to look at our statistics in isolation.”

Craig then provided the following data:

HE= “Humane Euthanasia”

| DOGS | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 YTD (through November) |

| Intake | 990 | 1152 | 1197 |

| Adoption | 715 | 748 | 937 |

| Transfer Out | 97 | 204 | 97 |

| RTO | 47 | 66 | 73 |

| HE | 89 | 133 | 138 |

| Died | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| HE Rate | 8.99% | 11.55% | 12% |

These results — and Mr. Craig’s care in introducing the numbers with a caveat about the ASPCA supporting the most “at risk populations” and his urging that we not “look at our statistics in isolation” — may help explain the ASPCA’s reluctance to share its data. For the HE, or “humane euthanasia”, rate of 12% is above what is generally considered to qualify a shelter as a “no-kill shelter.”

Asked how the ASPCA defines the dogs they choose for “humane euthanasia” and if he could provide a specific definition of the population of dogs “humane euthanasia” encompasses, Craig declined to be specific, saying only, “Each dog is treated as an individual with their own unique set of circumstances and conditions.”

Mary Smith of Maddie’s Fund, a foundation devoted to canine welfare, told the Washington Post in an interview that a shelter must have a 90% save rate to meet the definition of a “no-kill” shelter. According to no-kill advocacy group, Best Friends Animal Society’s website, a 90% save rate is a “benchmark for no-kill.” Making data about euthanasia (including data about animals who are physically healthy when they are euthanized) available to the public allows people to make their own decisions about the acceptable killing of animals. The ASPCA does not publicize which animals are at risk for euthanasia making it even more unclear why and when animals are killed.

Editor’s Note:

Below, we have published a letter from ASPCA spokesperson Alexander Craig taking issue with some of the points we made in the profile of the ASPCA’s animal sheltering program. His most important point is that we misconstrued the “HE” column in the data that he sent The Canine Review to mean “healthy euthanasia,” when, in fact, he asserts that it means “humane euthanasia.” Although others in the field to whom we have spoken did not recognize “humane euthanasia” to be what Mr. Craig calls a “universally recognized” definition for “HE,” we accept his definition, and we apologize for the error (which was the Editor-In-Chief’s, not reporter Julia Kott’s).

Accordingly, we have changed the text of the article, substituting “humane” euthanasia for “healthy” euthanasia. However, Mr. Craig does not contest the accuracy of the data, which, again, is the data he gave to us – and which puts the shelter’s euthanasia rate above 10%. Thus, we stand by our reporting — including our reporting that others in the field view a rate above 10% as exceptionally high, as well as our reporting of Mr. Craig’s explanation for the rate. Adjectives aside, we gave readers both sides.

We have also changed the sentence regarding behavioral rehabilitation centers to reflect Mr. Craig’s statement that the organization now operates only one such center.

Emily Brill, Editor-in-Chief

Here is Mr. Craig’s letter in full:

December 27, 2019

Hi Emily and Julia,

We are disappointed that you apparently failed to understand certain essential points about our overall operation. We were forthcoming with you and it appears that you set out to find issues that, in our view, contribute to an inaccurate picture of our organization. Most importantly, your article is significantly misleading by suggesting that we euthanize healthy dogs. The designation “HE” is universally recognized throughout the animal welfare industry to mean “humane euthanasia;” it is not healthy euthanasia. Please correct this and remove “healthy euthanasia” in your article and in all social media posts.

The ASPCA believes philosophically and we implement in practice at our Adoption Center that every effort should be made to place animals in safe, responsible homes. We have extensive programs in place to make this happen, but unfortunately, due largely to the nature of the population we serve, this is not always possible. Euthanasia should only be resorted to as a last-step option when necessary to spare animals from suffering.

Please also correct the following sentence: ‘It operates what it calls “Behavioral Rehabilitation Centers” in New Jersey and in North Carolina, where care is provided for animals who have been living in abusive conditions.’ The ASPCA operates one Behavioral Rehabilitation Center in North Carolina (a few years ago, we implemented a pilot program in NJ, which led to the permanent facility in NC).

Best,

Alexander Craig

Manager, Media & Communications

ASPCA